August 13th, 2015

It’s 7:00 am and I’m on a train bound for Preston, where I’ll connect with a second train north to Glasgow, and then a third train north even further to Stirling.

It’s quiet on the train – there are maybe half a dozen of us sharing this carriage, and nearly everyone is asleep. It’s a gorgeous morning, and the sun streaming in through the window makes me sleepy.

But I don’t sleep – much. The scenery outside the windows is stunning. The train runs along the east-west river valley, and passes endless ridges covered in sheep, rocky outcroppings, and a feeling of ancient mystery. Sometimes the ridges crowd right up to the train. Other times they fall away to reveal wide-open valleys, with small English country villages and towns nestled in fields of brilliant green.

It’s just after 8:00 am when I leave the English countryside behind and arrive at Preston rail station. On this Thursday morning, the station is alive with weekday commuters and early-morning tourists catching trains from at least a dozen platforms. Like most rail stations, it’s all grey – grey rails, grey buildings, even grey dust on the trains.

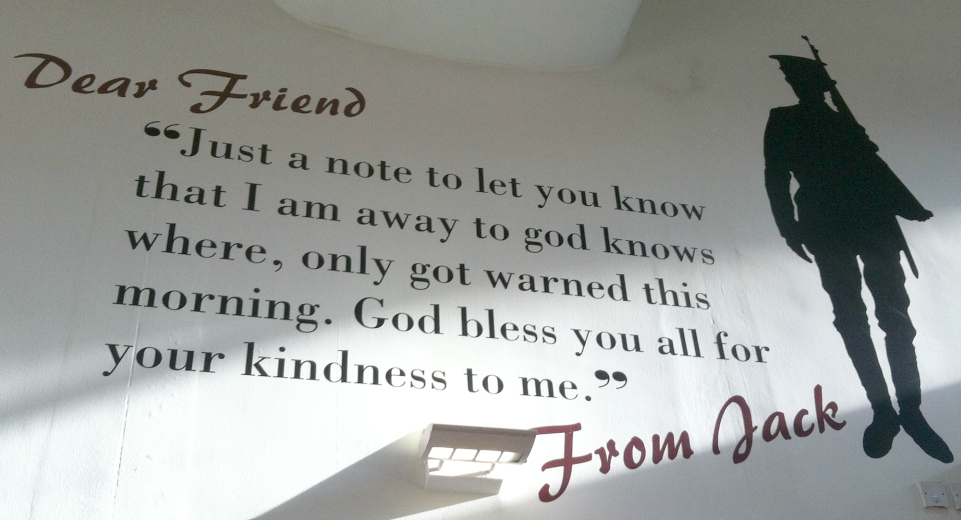

But when I step into the waiting room, I’m greeted with white walls, beams of sunlight, and the most interesting war memorial I’ve come across in some time:

There are several quotes like this on the walls, all above head height.

A gold plaque on the wall explains that during the Great War, the waiting room was used to provide a free buffet for the soldiers and sailors who were heading out to the front lines. The buffet was manned entirely by volunteers, and it was open 24 hours a day from 1915 to 1919, and then 14 hours a day from June – November 1919.

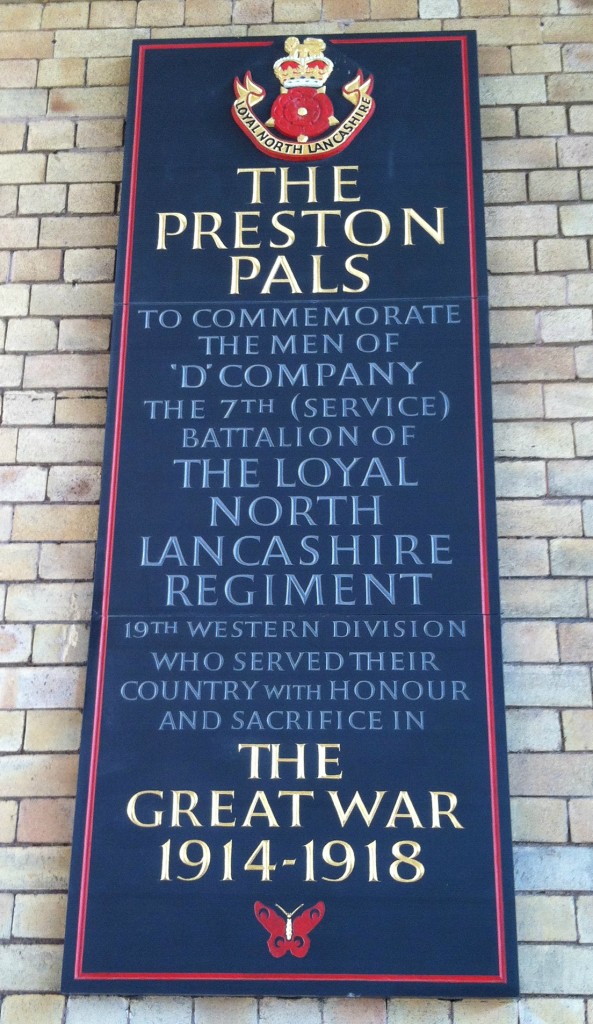

Outside the waiting room, another plaque commemorates The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, and reminds us that at least one of that regiment’s missing troops hasn’t been forgotten:

It’s a sobering reminder that although I tend to think of the world wars as belonging to my great grandparents’ generation, the memory of them, and the people who served and died in them, is still very much alive.

I spend about 40 minutes in the Preston waiting room before my train pulls in to whisk me away to Scotland. It’s a Virgin train, designed for cross-country and long-distance travel. This train is much, much longer than the regionals I’ve been taking over the last few weeks. There are at least 10 cars, a small onboard cafe, outlets at every row of seats, and onboard wifi (for a nominal fee).

There’s a woman sitting in the window seat that I pre-booked, and a couple across the table from me as well. I assure the woman next to me that I’d prefer the aisle seat, and she graciously removes her purse. As the train starts to pull out of the station, I pull out my laptop, feeling very business-like as I prepare to spend a couple of hours answering emails for work before I’m officially on vacation.

It doesn’t take long after leaving Preston for me to realize two things. First, the countryside is just as beautiful heading north as it was heading west. We’re running parallel to the ridges now, and they’re further away from the train. Even though we’re not across the border yet, I can’t help but think of the ridges as the forerunners of the glens and hills of Scotland.

The second thing I realize is that the train is going fast enough to sway slightly from side to side. The swaying, combined with looking at a computer screen, is giving me motion sickness. Luckily, there are a couple of times where the wifi connection drops out, and I take these short breaks to walk up and down the train.

Finally, the wifi gives out completely just as I finish my last email. I pack away my computer and scoot across to the empty forward-facing seats on the other side of the aisle. Almost immediately, the nausea dissipates, and I’m free to watch the Scottish countryside roll past the window as we approach Glasgow.

I don’t have a lot of time in Glasgow – only 35 minutes or so, and 20 of those are set aside to walk between train stations. I enjoy every minute of that walk – the city is alive with sunlight, street buskers, tourists, and Glaswegians on their lunch break.

I pass a TGI Fridays on the corner of the pedestrian mall, which seems absurdly out of place in Glasgow:

Five minutes later, there’s a commotion ahead of me, and these gentlemen are coming down the street:

As I approach the Queen Street rail station, there’s a small park across the street. A set of bleachers have been set up, and a section of the pavement has been cordoned off.

It’s one of several venues for Glasgow’s annual piping contest (bag-pipping, that is), and suddenly I realize that the troop from India must have just finished their performance. Unfortunately, there are no performances scheduled in this park until much later in the afternoon, and I have a train to catch to Stirling.

I experience a brief moment of panic at the Glasgow station, as there are no trains leaving for Stirling at the precise time listed on my itinerary, and I am traveling on a pre-booked, this-train-only ticket. Luckily for me, the conductor on the train bound for Stirling doesn’t seem to care if I’m supposed to be on this particular train or not, as long as I have a paid-for ticket.

It’s quiet at the front end of the front coach, and the noontime sun streams in the windows as we head northeast to Stirling. Despite my intentions to stay awake, my early-morning start catches up with me, and I slide into sleep.

Stepping out of the train station in Stirling, I feel free for the first time in weeks. The sun is shining, I have no commitments for three days, and there’s a brand new city – and country – to explore.

I heft my trusty Nike duffel bag and walk the 5 minutes to the Willy Wallace hostel, one of two hostels in Stirling. More than a decade has passed since my last European hostel experience, but I feel right at home as I plop my bags down on my bunk bed. Twenty minutes later, I’m ready to set off for Stirling Castle.

As I wind my way through the old parts of Stirling, I pass several interesting buildings, including the Stirling Highland Hotel,

the Ebenezer Erskine Memorial,

and the Old Town Jail.

Finally, just before I reach the castle at the top of the hill, I arrive at The Church of the Holy Rude.

Mary, Queen of Scots, had her son James VI crowned king of Scotland in this church in 1567. He was just 13 months old at the time, so he probably didn’t appreciate splendor of this medieval church, nor the fact that John Knox preached at his coronation ceremony.

What interests me about the church isn’t the inside, although it is beautiful. I’m fascinated by the rows and rows of gravestones behind the church.

Unfortunately, I don’t have time to look at them all – Stirling Castle will be closing in a few hours, and I want as much time as possible to explore it.

Luckily, the castle is only a few minutes’ walk up the road from the church. An imposing statue of King Robert the Bruce guards the approach.

Standing on the walls of Stirling Castle, it’s easy to see why Stirling is often referred to as the Key of Scotland. The castle is built on a hill in the middle of a very broad, very flat plain. You can see for miles in every direction, which was incredibly handy because any people or goods who wanted to travel east or west, north or south, had to travel through Stirling. Hence, he who controlled the castle controlled the kingdom.

Looking east towards the Wallace Monument, Abbey Craig, and the Ochils

Looking west towards the hills of Loch Lomond

The castle is crawling with tourists when I arrive. For a small place, there’s a lot to see: the Queen Anne Garden, the history museum, the royal apartments, the chapel, the main hall, the regimental museum. Luckily for me, there’s a free tour leaving in about 5 minutes, which seems like the best place to start.

Over the next hour, most of what I now know about Stirling Castle comes from Brian, pictured here at the start of our tour.

The earliest parts of Stirling Castle date from the 1400s, so it’s mostly a medieval castle. It was the seat of the Scottish royalty for several hundred years, most notably during the reigns of the James III – VI in the 1500s. James VI was also Queen Elizabeth I’s nephew, and when she died without any male heirs in 1603, James VI of Scotland also became James I of England.

After he was crowned King of England, the Scottish royal family moved south to England, and Stirling Castle became a military castle, rather than the seat of royalty. In fact, the castle remained in the hands of the military until the 1970s. They’ve done huge amounts of restoration work since then to bring it back to the way it looked during the reigns of James V and James VI.

After the tour is over, I revisit the royal apartments, where my eyes are drawn again and again to the bright bold colors of the various coats of arms, and the intricate paintings on the walls.

The unicorn of House Stuart and the royal Lion Rampant of Scotland

The Lion Rampant of Scotland

Vibrant wall painting in the Queen’s receiving room

Exploring the royal apartments gives me a visceral appreciation of how far above the average peasant medieval royalty lived. Most of the people living in the time of Mary, Queen of Scots had thatched roofs and dirt floors covered in reeds. Houses were small, cramped, and smoky, and animals often lived in or near their owners in the winter.

Contrast that with this palace, which is already a huge building of stone, with ceilings that go up and up forever in comparison to most houses of the time. The floors are stone, not dirt, and there’s brilliant color and decoration everywhere.

It’s not hard at all to see how places such as this were necessary to proclaim one’s superiority over one’s subjects. Despite the dangers of being nobility or royalty, I too would fight tooth and nail to live in a place like this if I’d lived back in the 1500s!

After leaving the royal apartments, I revisit the main medieval hall,which is the only building on the castle grounds that has been restored to the brilliant, warm yellow coating that would originally have been on all of the buildings.

The gold whitewash may not look like much, but when the sunlight catches it atop the hill, you can see that golden color from miles away in the surrounding countryside.

The Great Hall was the site of many feasts, including one where a full-sized ship, complete with cannons, was used to bring in all kinds of seafood dishes. If you think Hollywood celebs do crazy things today, they have nothing on medieval kings in terms of doing outrageous things with food. Nothing was too much work for their servants, and nothing impressed your guests more than showering them with food, the very substance required to sustain life.

Next to the Great Hall is a small chapel, where at least one of the James was baptized. It’s a small little place, rather intimate. What caught my eye the most were these gorgeously embroidered alter clothes

After my visit to the chapel, I spend some time exploring the grounds and outer fortifications.

And of course, no visit to a castle is complete without a medieval version of shutes & ladders called The Seige Game.

It’s now just after 5:00 pm, and it’s time to say goodbye to Stirling Castle. I’ve spent the last 4 hours immersed in Scottish history, the lives of the various King James, and how awe-inspiring the entire castle complex must have seemed to ordinary people who lived in the 1500s.

It’s time to finish my castle experience with a quick visit to Argyll’s Lodging before the doors close in a few minutes. Argyll’s Lodging is a 17th-century townhouse at the foot of the approach to the castle, and admission to the Lodging is included in my castle ticket.

I get lucky – I sneak in just as the doors are closing. Unfortunately, I’m so saturated with history that although I want to take in every detail of this marvelously restored townhouse, most of it washes right over me.

However, I do stop to appreciate the main hall:

and also this ridiculous chair/loveseat/throne in the drawing room.

As I leave Argyll’s Lodging, the church bells are ringing the hour: 6:00 pm, the time when every tourist attraction in Stirling (and Europe) closes.

However, there are still about 3 hours of daylight left, and it’s too marvelous an evening to go back to the hostel or waste it inside a restaurant. Instead, I set off to explore.

I take the path down the hillside from the castle and find myself on a road called Ballengeich Pass. After a few minutes, I come to a modern cemetery. Walking path signs nearby tell me that I’m on the Gowan’s Hill Heritage Trail. The trail is far too tempting to resist . . .

A few minutes later, another information sign informs me that if I follow the Gowan Hill Heritage Trail, I’ll find the beheading stone used by Stirling Castle’s inhabitants to decapitate their victims.

Sure enough, I find the beheading stone on the east side of Gowan’s Hill.

The stone isn’t much to look at these days, but the view from this promontory is incredible.

I sit on a bench near the beheading stone for nearly half an hour, basking in the early evening sunlight, enjoying the view, and letting my mind half-imagine what Stirling town, castle, and the surrounding countryside looked like when the stone was actually in use.

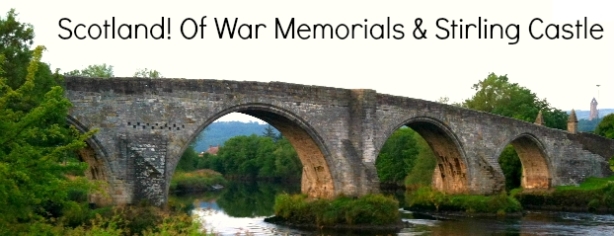

Finally, I decide to keep exploring. I make my way down Gowan’s hill and find myself at Stirling Bridge, which is where William Wallace (Braveheart, anyone?) defeated the English.

A sign on the far side of the bridge reads:

In early September 1297 a mighty army arrived in Stirling to put down

Scots resistance to English rule. The Scots allowed around half the invaders

to advance across the narrow bridge over the Forth. Then William Wallace

and the Scots swept forward to achieve a brilliant victory over a far-superior force.

In William Wallace’s time, the ground on the east side of the bridge was so boggy that a causeway extended from the foot of the bridge until the ground was firm enough to support horses and heavy wagons. A town was built where the causeway ended, and they called it Causewayhead.

As I walk along the modern road into Causewayhead, I pass rows of individual homes, townhouses, and quite a few B & Bs, all of which say “No Vacancy.”

The purple trim on this house catches my eye:

It’s unusual to find purple as an accent color on a home, especially in conservative England. My mother would love it.

The road leads straight to the Wallace Monument, which dominates the skyline no matter where you are in Stirling.

It’s far too late today to go inside. The sun is setting, and it’s time to head back to the hostel and get some dinner.

Tomorrow, I’m headed to the Battle of Bannockburn to learn all about Robert the Bruce. And, I’ll be back to the Wallace Monument.

The “Holy Rude” graveyard, both old & new, looks like it would be an interesting walk. Unfortunately, I’ve no surnames to pass on to look for in that area — very few of your mother’s side distant ancestors meandered into Scotland.

The Stewart, or its French equivalent Stuart, is an interesting line. Easier on the ear than “stigeweard”, its Old English origin, or fitz Flaad, the line’s progenitor. The Royal line is of the “Celtic clade” — since the line came to the UK with the Norman Conquest, that would make the progentior a Briton Celt…

Also interesting is what the Scots choose to honor in their monuments, though Stirling being a royal area would steer memories in that direction…

Pity we don’t have any close ties to Scotland. The bit of it I saw around Stirling is stunning, and the people are incredibly warm and friendly.

I don’t know why, but fitz Flaad doesn’t do anything for my ears at all. At least Stigeweard sounds like it would be ferocious if yelled on a battlefield.

I always find monuments fascinating, not just for what they tell us about history, but that someone felt it important enough to mark that particular bit of history. Maybe someday I’ll start setting up my own monuments and memorials, to commemorate whatever history I think is relevant.

Monuments (and stories) are normally built/told by the winners. Not-so-much in Scotland — heroic figures seem to capture their attention.

Not much above the Midlands in our ancestral background. Swineshead in Lincolnshire (East Midlands) is an ancestral focus. Much more in the south (West & East Sussex and southwest (Devon & Somerset).

Greystoke (castle) in Cumbria is the (ancestral) farthest north that I know of.

“Monuments”, especially in the distant past, appear to be attempts at immortality — being remembered as their bodies turn to dust.

Not-so the Celts, both Islands & Continent. They believed in reincarnation, and Bards, the first druidic “stage”, provided the doorway into their rebirth. Well-born with heroic songs, extremely low-born with tales of cowardice, betrayal, etc. Northern continentals, sometimes labeled “germanic” had the songs, but not the reincarnation.