July 24, 2016

It’s not quite noon as the tour bus pulls away from Glendalough, and already I feel full to the brim. Running on little sleep and an early morning adventure getting to the tour bus, I’d like nothing more than to take a nap as we climb higher into the Wicklow Mountains.

But the beauty of the Wicklow Mountains, and our guide’s interesting stories, are too good to miss.

Not far from Glendalough, our guide points out the remains of a lead mining village built in the 1800s over one of the many ore seams running through these hills. When the seam was exhausted, the miners simply left their village behind and moved on to greener pastures.

Several hiking trails lead through these ruins. A handful of day hikers are exploring the ghost town. I long to be one of them. Like Glendalough, this place exudes mystery and stories waiting to be told.

As we continue to drive through the Wicklow Mountains, our guide (and later research) fills me in on the importance of these mountains. They are the largest continuous upland area in Ireland, and the source of most of the lead, copper, iron, sulphur, gold, silver, and zinc that was mined in Ireland. The gold rush was short-lived in the late 1700s, and the last lead mine closed in 1957.

The mountains are mostly granite, which has been quarried over the years for buildings in Dublin as well as around County Wicklow. Several of Ireland’s important rivers have their headlands in these mountains, which are full of small lakes carved out during the last ice age.

These lakes and valleys were also a great hideout for two of Ireland’s Gaelic clans: the O’Byrnes and the O’Tooles. Kicked out of their lowland lands by Strongbow in the 1100s, these clans took to the mountains and used them as a base to harass the English for centuries. Finally the English stripped them of their land altogether in 1652, and that was the end of the terra guerre (land of war).

With the clouds hanging low over the hills, it is not difficult to imagine Gaelic warbands descending from these heights to raid the English.

It’s beginning to rain as the bus pulls into a scenic outlook. We’re high up in the mountains now, and the feeling of being a very small part of a very big world is palpable.

The clouds are so low we could almost jump up and touch them, and the distances across the valley feel small only by comparison to the endless sky.

As we pile back onto the bus, I stop to ask our guide about the stands of pine trees growing intermittently on these bare hilltops. Before WWI, these mountains were covered in deciduous forests. Ireland’s contribution to the war effort was to harvest these forests as fuel for England’s great wartime factories.

After the war, the country’s focus was on its newly granted independence, and no plans were made to replant the deforested mountains. Eventually a lumber company purchased the rights to grow and harvest lumber, and they planted Scotch pine, which grows quickly and is easy to harvest. Aside from these commercial groves, the mountains remain bare of trees.

The mountains aren’t bare of vegetation, though. It’s the height of summer, and most of the heather are just beginning to bud out in their distinctive purple haze.

Come August and early September, these hills will be a riot of green and purple. As I try to imagine these hills decked out in their autumn colors, my eyes close and I slide into sleep.

I awake an hour later to the crackle of the tour bus PA system. We’re approaching the medieval town of Kilkenny, our final stop on today’s adventure.

I know nothing about Kilkenny, but my first view of the castle and the long line of busses we pass before finding a parking space are good signs.

The streets are crowded with tourists as we follow our guide on a walking tour of the old town. It’s not as crowded as it will be in August, when all the schools go on summer holidays, but our guide is already lamenting the hordes of tourists.

It doesn’t affect his presentation, though. For the next hour, he delights us all by pointing out local landmarks, explaining the history of Kilkenny, and sharing a few stories as only the Irish know how.

Like many Irish settlements, Kilkenny began as the site of St. Canice’s church, built in the 6th century and evolving into a major monastic settlement by the 8th century. It was also the chief town in the kingdom of Osraighe, which was anglicized to Ossory, the name of the diocese that governs St. Canice’s.

Unfortunately for the Irish, the leader of Osraighe in 1169 was Domhnall Mac Giolla Phádraig. He fought against the Normans several times between 1169-71, but was defeated each time and ultimately had to swear loyalty to Strongbow and England’s King Henry I. Not long after this, Strongbow appears to have kicked Domhnall out of Kilkenny entirely, realizing that it needed to be fortified by the Normans in order to control the crossing of the Nore River.

Gaelic warriors destroyed Strongbow’s fortification a couple of years after its construction, but that didn’t phase the Normans. Strongbow’s daughter married William Marshall, who simply rebuilt the castle (this time in stone) in 1213.

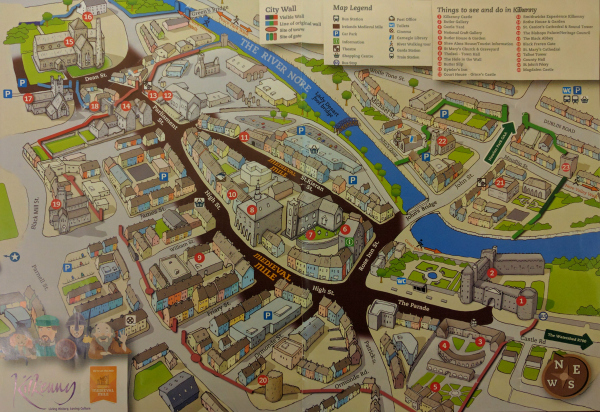

As William Pembroke, 4th Earl of Pembroke, set about making Kilkenny the principle seat of his southern lands, the town split between the Norman-English settlers and the native Irish. “Hightown” centered around the castle on its hill and the medieval mile, enclosed with town walls on three sides (the fourth side being the river Nore itself). Earl Pembroke issued a town charter in 1207, which would stand until Kilkenny was upgraded to a city by King James I in 1609.

“Irishtown” became everything outside the city walls and centered on St. Canice’s church, which by now had become a cathedral. Irishtown looked to the bishop of Ossory at St. Canice’s cathedral for governance, while Hightown looked to the English living at the castle. Even today, our guided tour emphasizes several times the subtle power struggles that occurred between the two cultures.

Fast forwarding a bit, Kilkenny appears several more times in the history of Ireland. The first is in 1367, when the Statues of Kilkenny were passed by the English king. The king was highly displeased to hear that most of the English in Ireland had turned “more Irish than the Irish” and were in danger of forgetting their loyalty to their homeland.

The Statues of Kilkenny cracked down on this practice by forbidding marriages between the English and Irish, using Irish names or clothing, or fostering Irish children. All English landowners were required to learn and speak English on danger of losing their lands. And the Irish sports of “horling” and “coiting” were replaced by archery and lancing.

Kilkenny’s second claim to national historic fame came in 1641, when the Irish tried to seize control of Ireland with the aim of forcing concessions for Catholics. The coup d’état failed, but the rebellion grew into a fight between the Irish Catholics and the protestant English and Scots. Kilkenny was the center of the Catholic Confederation, which essentially ruled most of Ireland until the Cromwellian invasion of 1649 put an end to Catholic rule.

Kilkenny’s third contribution to Irish history occurred in the winter of 1689-1690 when it played host to the disposed James II of England. James II was Catholic, and had been kicked out of England by the English lords who were offended by James II’s religious fervor and pro-French tendencies. Much of Ireland was Catholic, however, and rose up to support James II. Unfortunately for the Irish, James II was defeated at the Battle of the Boyne and ran off to Europe with his tail between his legs.

Today Kilkenny is still called a city, although it’s more the size of a town. It takes about an hour to wander through its narrow streets.

As we pause outside Kyteler’s Inn, our guide switches from political history to witchcraft. This Inn was once home to Dame Alice Kyteler, the only child of a prominent Norman merchant family. Born in 1280, by the time she was forty Dame Alice had been married four times, and each one of her husbands had died. Some say the townsfolk were the first to cry witchcraft, and others say it was Alice’s ten children who were anxious to get their hands on their mother’s sizeable fortune.

Either way, in 1320 Alice became the first recorded instance of someone tried with witchcraft. She was convicted, but used her connections to escape the country with her maid’s daughter. She left her maid Petronilla behind, and poor Petronilla was forced to make a public confession before being burned at the stake.

Although this story is nearly 700 years old, it’s clear that my guide still resents the fact that wealthy, English Alice got away scot-free while her poor Irish maid was left behind to be whipped and burned alive.

Our tour ends outside the courthouse, also known as Grace’s Castle.

The courthouse was built over a 13th century fortress (Grace’s Castle) and includes the remains of the 18th century jail. The basement windows, sunk below street level and barred with iron, are former jail cells which held many prisoners throughout the centuries. Inevitably, most of those prisoners were Irish, and weren’t often treated very well by the English authorities.

But instead of begging or bribing the English jailers to treat their loved ones well, a group of locals got together and started to spread a rumor that the ghosts of previous victims haunted the alleyways of Kilkenny in search of revenge. The locals were so convincing that the English jailers were afraid to be out alone at night, which cut down on the worst of their drinking and ensured better treatment for the prisoners.

To the left of the courthouse is the Smithwick Experience, Kilkenny’s internationally famous brewery that started nearly 300 years ago. Founded by a Catholic at a time when Catholics weren’t allowed to own property, run for elected office, or join the armed forces, Smithwick rose from a small-town brewery to international fame as Ireland’s #1 ale in the 1900s. Today it’s one of Kilkenny’s major attractions.

Head full of history, our guide releases us to explore on our own for the next two hours. It’s a beautiful partly sunny afternoon, and it feels good to slowly retrace our route back up to the castle. I can’t resist stopping into the local bookstore, and happily come away with an intriguing title to add to my collection.

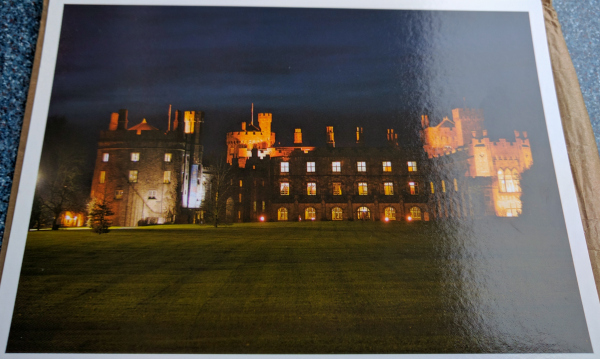

Once at the castle, I am suitably impressed. It is easy to see that William Marshall meant business when he designed this castle in the 1200s.

Three of the four original medieval towers remain, including the south tower.

Originally there was a fourth wall where I am standing now, enclosing the entire courtyard. It was damaged by cannons during the Cromwell’s invasion in the late 1600s, and was torn down soon afterwards.

Inside, the castle is more elaborate townhouse than medieval fortress. Each wing of the building leads to long galleries, with rooms branching off to one side and a fine view of the courtyard on the other. The rooms are sparsely furnished, with the usual hand-blocked wallpaper and faded tapestries. The décor doesn’t strike me as particularly outstanding until I learn that nearly the entire contents of the house were sold in the 1930s. Everything I’m seeing in the house today is either a recreation or something that wasn’t worth being sold.

In fact, the story of Kilkenny Castle is rather remarkable. After its initial construction by William Pembroke, the castle passed through all five of his sons before passing into the hands of one of his daughters. Eventually the family must have moved out of Kilkenny, because they sold it to James Butler in 1391.

The Butler family, as described by my guide and later research, are better known to history as the Earls of Ormond. They were one of Ireland’s most powerful English families during the 1500s, and it all began because Theobald Fitzwalter had a knack for organizing provisions.

When Theobald Fitzwalter arrived in Ireland in 1185, Prince John (eventually King John of Robinhood fame) gave him land and appointed him Chief Butler of Ireland. That meant Theobald was in charge of providing food and drink whenever the Prince arrived in Ireland. It also meant that he was entitled to 15% of all the wine that was imported into Ireland, an honor the family would hold until the English Crown bought it back in 1811.

Over the next two hundred years, the Butlers used the income from their wine and their friendship with the English royal house to become one of Ireland’s most important families. In the 16th century, Margaret Butler married Sir Thomas Boleyn. Their granddaughter Anne became Henry VIII’s second wife, and their great-granddaughter was Queen Elizabeth I.

During the time the Catholic Confederation ruled Ireland from Kilkenny, James Butler had at first tried to negotiate with King Charles I on behalf of the Irish. Then the English executed Charles I, and James had to flee to France along with Charles’ son. Kilkenny Castle was confiscated by Parliament, who then returned it to James’ wife Elizabeth based on her appeal that she was the rightful owner of the estate.

When Charles II was invited to return to England, James Butler accompanied him and was elevated to the title of Duke of Ormonde. Having spent time in France, James did a lot of remodeling to make the medieval castle look more like a French chateau. He also must have passed on some wisdom to his descendants, because his grandson, another James Butler, sided with William of Orange during the Jacobite uprising and came through with properties, title, and wealth in tact.

Kilkenny Castle remained the family’s home until the 1935, when the Butlers could not longer afford the upkeep and inheritance dues. The family put up the contents of the house for auction and moved to England. In 1967 Arthur, 6th Marquis of Ormonde, sold the castle to the people of Kilkenny for £50. Mick Jagger showed up for the party that was held to transfer ownership to the city. When asked why, he apparently said “I heard there was a party!”

Reading between the lines of family history, it’s clear that the castle was in terrible shape when it was sold to the town. Nearly all the furnishing were gone, and signs along one of the galleries shows in detail the restoration work required to restore basic infrastructures like floors and windows.

While some of the rooms are starting to come together, it’s clear that the first priorities for restoration were the formal gardens,

and the Great Hall.

Filled with portraits of the Butlers and a few English Kings, the Great Hall runs the entire length of the east wing. Its length and opulence remind me of the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.

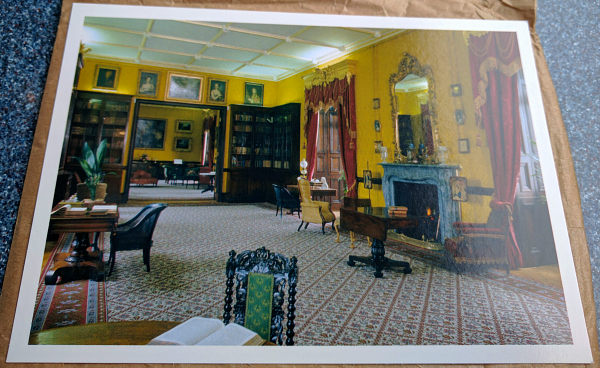

My favorite room in the castle is the library.

Not only does it smell of old books, but the bright yellow of the walls and the opulent décor bring the 1800s Butler family to life in my imagination. What a pity the house was allowed to fall into ruin!

I wish I had more time to explore the park that runs south from the estate along the river. Unfortunately, it’s time to board the bus back to Dublin. This time I fall into a deep slumber, allowing dates and impressions and stories to sort themselves out as I sleep.

When we arrive in Dublin, I thank our guide for an unforgettable day. His stories and passion for the history of Ireland really brought Glendalough and Kilkenny to life. He clearly loves what he does and loves sharing it with tourists. He even got us all singing as we drove into Dublin – no small feat for a man who claims to have a terrible voice!

I spend my hour-long layover in Dublin walking slowly up and down the Liffey. My senses are entirely too full to take in any more today. I’m content to let the late afternoon sun spill over my face and arms and watch the seagulls.

The bus ride back to Belturbet seems to take longer each time, but I arrive home just before 10 pm, a bit of daylight left on the horizon and a few minutes to panic about a broken converter before a scheduled call with some friends back in the US.

I’m completely knackered by the time I fall into bed. It’s been a long weekend but a good one. It bodes well for next weekend, when I plan to cross the border and enter Northern Ireland for the first time.

Up next: a walking tour and first impressions of Belfast.

Sad to see the deforested hills — makes imagining them in the distant past more difficult…

A nice historical summary — interesting how the 30-years-war on the Continent played out in Ireland.

Any “BCE” memories from the guides, etc — “myths & legends” vs somewhat historically documented? Celt presence in Ireland is noted back to 500 BCE, though (they’ve) probably been there almost 2000 years longer.