August 18 – 21, 2016

The National Museum of Archaeology is one of my favorite places in Dublin. It’s free (always a plus) and its collections include prehistory, Celts, Vikings, church history, and much more. There’s even an exhibit on ancient Egypt and Cyprus!

Like the Book of Kells, I’ve been here before. I know Zephy’s interest in museums and history isn’t as high as mine, so I’ve narrowed down our afternoon visit to the absolute must-sees: Celtic gold, the Viking exhibit, and the bog bodies.

We start with Ór – Ireland’s Gold, a collection of prehistoric goldwork from 2200 BC to 500 BC.

From the moment I see the first gold horde, I am delighted.

There are ear spools, which go in the flesh of the earlobe instead of dangling from it.

There are gold collars,

gold bracelets,

and gold necklaces.

My favorite pieces are these delicate earrings

And these amber and gold beads, most likely from a necklace.

At one end of the gold exhibit is something completely different: a 45-foot long canoe hallowed out of a single oak tree.

It runs nearly the entire length of one wall. The Lurgan Canoe was found in 1901 in a lake that had once been a bog. It’s narrower on end and wider at the other, and there are several raised ridges in the boat’s bottom to suggest some sort of division of space. The canoe is over 4,000 years old, older than much of the gold work I’ve just been admiring.

Oddly, no one seems to know exactly what the canoe was used for. From its size and craftsmanship, the general consensus is that it’s too fancy to have been used as a simple fishing boat. Current theories include making the boat for a ceremonial purpose or a trading expedition. Or, it may have been joined to a second boat to make a catamaran capable of sailing the open ocean.

From the gold exhibit, we climb the marble stairs to the Viking exhibit on the second floor.

I like the look of the side-blown and end-blown horns, which are nearly always found in pairs and are Ireland’s oldest known musical instruments.

There are quite a few different swords on display, from Bronze Age swords not much longer than a forearm

To the more modern swords that were in use in the 1000s (and possibly even at the famous Battle of Clontarf).

An information sign next to these blades states that one of the blades carries the inscription “SINIMIAINIAIS” which is “apparently meaningless.” Maybe I’ve read too much Tolkien, but it’s hard to believe that someone would take the time to inscribe a meaningless word on their sword.

Of all the items on display, my favorite is the bronze shield. Its studded ring design reminds me of the gold collars I saw earlier.

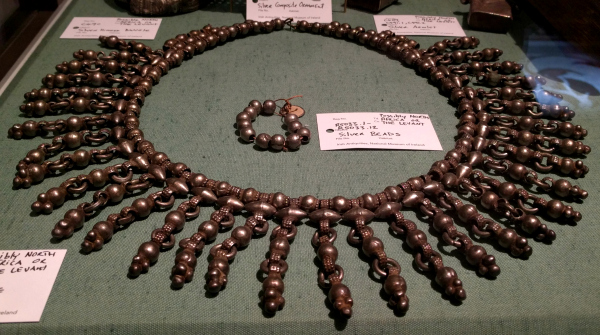

From Viking Ireland, we briefly take in the medieval church exhibit. It’s mostly croziers, reliquaries, and elaborate church vessels, but this silver necklace is stunning.

Its information sign says its origin is “possibly North Africa or the Levant.”

There’s a lot more to see at the museum, but we’re running out of time and attention. I direct us to our last exhibit of the day: “Kingship and Sacrifice.”

The exhibit is well done, with glass cases containing all sorts of royal regalia and trappings of daily life for an Iron Age man. In the center of the hall are four round rooms, open to the ceiling and accessed by a short ramp.

These house the four bog bodies, each found perfectly preserved in a peat bog. Most of the bodies are not complete, either due to trauma at the time of their discovery, or because they were found in an incomplete state.

What makes the bodies absolutely remarkable is that the bog has preserved much more than their bones. You can see skin, hair, fingernails, internal organs, and much more. It’s difficult to believe that these bodies are 2,500 to 3,000 years old.

The first time I was here, the one that got to me is the one they call Oldcroghan Man. And today is no different. Of the four bog bodies on display, he’s the one I remember long afterwards.

Oldcroghan Man has no head, and nothing below his waist – just a powerful torso and long arms. He most likely lived between 362-175 BC, and was over 25 years old when he died. They think he was a man of high social rank, as his fingers weren’t calloused and his nipples had been cut off, rendering him ineligible for kingship in the afterlife.

What really gets to me are his fingers. He has strong, powerful arms and his hands are perfectly preserved. The skin on them is preserved too, a dull brown that glints copper and iridescence in the low lighting. I’m fascinated by the fact that I can see his fingernails, and the leather torque wrapped around his upper arm.

I can’t help wondering who this man was, and whether he was a bad guy who got what was coming to him, or a good guy who was in the wrong place at the wrong time. I like to think he was a good guy, but there’s absolutely no way of telling.

Zephy is quite moved by the four bog bodies. He takes many pictures of each, exclaiming over the hair on one and the way they look alive in the low lighting. Something about taking pictures bothers me, but it’s not until I take a couple pictures of Oldcroghan Man that I can finally put my finger on why.

I can’t deny that seeing his body is a powerful experience. But I also feel like I’m seeing something that I was never meant to see. This body was a person once, and so were the other bodies on display. However they died, they were buried and left to an eternal sleep. We’ve interrupted that sleep, and I’m not sure the advantages of putting them on display outweigh the human decency of leaving their remains in peace.

– –

Zephy and I are quiet as we leave the museum. It’s been a long, full day of taking in history at the Book of Kells and here at the museum. Even though it’s raining off and on, we take the long way back to the train station. We wander through Temple Bar, stopping at a sweets shop, which smells of sugar and chocolate on this rainy afternoon, and a game shop with the newest Catan expansion pack displayed in the front window.

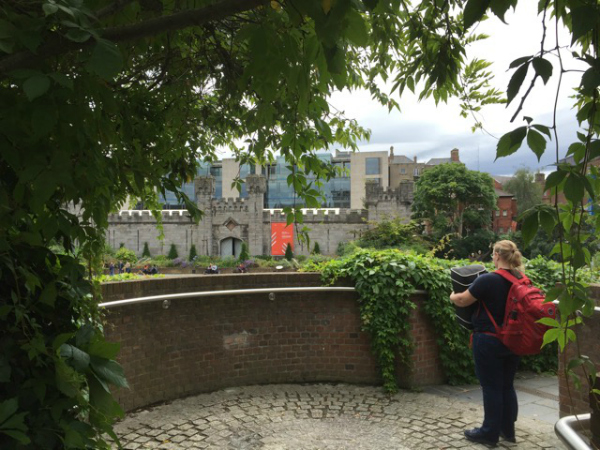

We go west as far as Dublin Castle, which looks quite forbidding in the grey afternoon.

Photo credit: James McKanna

We head back along the north side of the river, crossing over the historic ha’penny bridge

Photo credit: James McKanna

And passing Daniel O’Connell’s iconic statue at the head of O’Connell street.

We spend a quiet night in Maynooth, treating ourselves to dinner at an Indian restaurant instead of the tuna sandwiches we’ve been making in our room.

– –

I’m up early on Sunday morning, the same way I’ve been up early every day since arriving in Maynooth. Zeph is a night owl by inclination. His jet lag has been sending us to bed at normal hours, but even so I’m pleased that my body has gotten into the rhythm of getting up between 8 am and 9 am.

Today’s schedule has been something of a challenge: we need to check out by 10 am, and our train to Sligo isn’t until late afternoon. That gives us several hours to do something in Dublin.

There’s just one problem: nearly everything is closed on Sundays. And the things that aren’t closed completely only open around 1:00 pm.

Luckily, I’ve remembered the name of the library/museum near the Dublin Castle that I liked so well on my last visit. We check out precisely at 10:05 am and head straight for the Chester Beatty library.

We get there well ahead of their 1:00 pm opening time, which gives us plenty of time to explore Dublin Castle and the Dublin Gardens.

I get a couple of great shots of the castle, including the Treasury wing

and the Record Tower (named for its original function of storing records).

Behind the castle are the Dublin Gardens, built over the sight of the Dubhlinn, which was a black pool from which the city of Dublin took its name. Today it’s a beautiful helicopter pad with gardens around the edges.

Photo credit: James McKanna

A police garden in one corner honors those who have given their lives to their profession.

Photo credit: James McKanna

The glass plate slicing through the concrete wall is meant to represent the way in which one’s life can be sharply and completely interrupted.

Even with our slow exploration of the gardens, we have plenty of time to kill. The sun’s trying to come out, so we find a table on the castle café terrace. Over a mid-day snack of tasty pastry, Zephy and I take turns reading stories out of the Wild Irish Women book I picked up yesterday at the museum gift shop.

I especially like the story about a woman who pretended to be a man because that was the only way she could be a doctor. Dr. James Barry eventually became Inspector-General of British Hospitals – the highest position a doctor could obtain in 1850s Britain. Apparently it wasn’t until after her death that the rumors about her effeminate nature were verified – Dr. James Barry was, indeed, a woman.

Finally it’s 1:00 pm, and the doors to the Charles Beatty library are open. Born in 1875 in New York, Chester Beatty was fascinated by minerals, Chinese snuff bottles, stamps and – most importantly – manuscripts. He traveled widely and collected manuscripts from all over the world. He was fascinated by the beauty of them but also their historic value.

When he died, he bequeathed his entire collection to a trust to benefit the public. Today that collection is housed in the Chester Beatty Library on the Dublin Castle grounds. And specifically because of the terms of Chester’s will, the library is free to the public.

Two years ago, I stumbled across the library largely by accident. I remember spending a wonderful afternoon listening to Christmas carolers in its atrium and wandering through gallery after gallery of beautiful books and book art.

Today, we’re especially lucky: the first gallery is full of ancient Japanese scrolls and several magnificent – and old – versions of the Qur’an.

Pictures are strictly prohibited in the gallery, and there are guards at regular intervals. So you will just have to trust me when I say that I’ve never experienced anything quite like it. The exhibit is called “Lapis and Gold: The Story of the Ruzbihan Qur’an.” Some of the books, Qur’an and otherwise, are fabulously decorated: with lapis lazuli, with gold, with gems as thick as my fingers.

The Japanese scrolls are just as interesting, the way their pictures and characters flow from one scene to the next. Several of the Japanese texts are internationally famous. I don’t recognize them, since I’m not into Japanese literature, but they are beautiful. There’s a small section on books from Persia in one corner, and a full suite of Samurai armor in another.

Afterwards, as we’re headed to the train station, Zephy and I cannot stop marveling at the craft and workmanship that went into those manuscripts. Perhaps even more amazing, they are all from the library’s own collection. Chester Beatty sure knew a thing or two about buying – and preserving – beautiful things.

As we meet Jill at the train station, I’m feeling satisfied and pleased. It’s rare that I get to play local tour guide, and watching Zephy’s reaction to some of my favorite Dublin sights has been very rewarding. I’m especially pleased that I remembered the Chester Beatty library. I had a feeling Zephy would really like it, and I was right.

The train heads west, past our stop at Maynooth and out into the rolling fields of Ireland. In a few hours, we will pull into Sligo, and the next part of our adventure will begin.

Next up: To Every Thing There Is a Season

Sacrifice, punishment, the “loser” in contention for a high seat? A lot of speculation on “bog bodies”, and a lot of similarities between those on the “islands” and their continental counterparts.

Perhaps all-of-the-above — superstition like jamming stones into mouths during burial to prevent “vampiric resurection” to just a “convenient place to get rid of a body”…

Definitely a shame that DNA tests can’t be performed (the bog messes up DNA)…

Any inscribed sword, especially if that inscription is with silver inlay, is not “apparently meaningless”. It most likely is similar to the “Ulfberht” swords with a superior steel content apparently produced by a German monastry.

Whatever the reason for inscription, it definitely wasn’t meaningless at the time — the museum should be ashamed to write that on a placard…

A nice selection of bronze/iron swords. Ideally the bronze should be tested to see where the tin (or arsenic in older bronze) came from — copper was mined early in Ireland.

A surprising amount of alluvial gold in Ireland, which would account for all the gold shown. Especially interesting are gold collars (open in back) and torc’s (open in front), as they have a history and similarity to Gaul & Iberia, Greece, Thrace, and Western Asia.

Yes, there is a great deal of speculation over what the bog bodies tell us about their times and culture. Still, it’s amazing what we do know about those cultures – I would guess it helps that many cultures shared similar beliefs in things like burial and the afterlife.

I thought it was really weird for a museum to dismiss an inscription as “apparently meaningless.” It’s one thing to admit that you don’t know what it means, but to discount it seems quite silly. Maybe they were afraid of being seen as too “Lord of the Rings” fanciful? Even so, they struck the wrong message.

The gold and the swords are quite excellent. Ireland, like England, requires archeological presence whenever they build new buildings. And since a lot of new buildings went up in Dublin and Ireland in the 1990s and early 2000s, the museum has a marvelous collection. Even though gold doesn’t go well with my skin tones (too much yellow in them), I would still love to wear some of that jewelry (though not the ear spools that go in one’s earlobe).