August 13, 2016

It’s just past 3 pm when I get off the local bus in Blarney Village. There’s about a dozen of us milling about the sidewalk, and we’re all here for one reason: to visit Blarney Castle and kiss the Blarney Stone.

It’s a 5 minute walk from the bus stop to the main entrance, a small building at the end of a dead-end lane. Even though it’s Saturday afternoon, there’s hardly any line and I’m through in just a few minutes.

I follow the River Martin into the castle grounds,

cross a pretty bridge over the Blarney River, and there across the open lawn is Blarney Castle.

The field is dotted with statuesque cherry trees and flowing willows along the banks of the Blarney River. It’s a gorgeous open space, and yet I’m completely captivated by the castle itself.

Photo credit: postcard from Blarney Castle Gift Shop

I cross the Blarney River and immediately I’m at the foot of the castle. I look up. And up. And up again.

A seam runs down the middle of the tower, flanked at the top by two stately windows that are fancier than the simple rectangular ones in the rest of the tower. Three large holes just left of the seam mark the location of the garderobes, and a fancy columned window protrudes from the right side.

Cut into the rock in front of me are a series of small cells branching off a tunnel into the heart of the cliff. They look exactly like what they are: dungeons!

To the right are a series of caves.

According to legend, three passages lead away from Badger’s Cave: one to Cork, one to Kerry, and one to the lake at the edge of the property. The castle garrison used this cave to escape from Cromwell’s general, Lord Broghill, in 1646.

Legend also says that when Lord Broghill arrived at the castle, he expected to find the lord’s stash of gold plate inside. But it too had disappeared. Some say the treasure is stashed somewhere in the tunnels. Some say it was sunk in the lake. No one really knows for sure, and no one has been able to find either the treasure or the tunnels.

From Badgers Cave, it takes two, maybe three minutes to reach the lookout tower.

It’s in good shape – the information sign says it was probably restored in the 19th century. But it’s easy to imagine that at one time a curtain wall enclosed the castle and incorporated many towers just like this one.

The path is rising now, climbing around the limestone cliff to the top of the hill. It’s a moderate gradient, but I can imagine it would a different story if I were an attacking army weighed down with armor and weapons.

The east side of the castle is nearly as imposing as the north wall.

But it’s the tower that really captures my attention.

The Court and its photogenic tower are nearly all that remains of a Gothic mansion built by the Jefferys family in 1739. Apparently they found the castle itself too uncomfortable and built this mansion onto the east side of the castle instead. The mansion burned down in the 1820s and most of it was sold off to be used in other buildings.

I have plenty of time to admire the Gothic tower as I wait in line to enter the castle. Just outside the castle doorway, a sign informs me I’m standing on the oubliette. It’s a good old-fashioned trap door that, when opened by a guardsman, would drop an unwanted guest into a 50 foot pit with no way out.

The sign goes on to say that some historians think the pit was used as a granary, but given the intimidating “thou shall not pass” vibe coming off the castle, the trap door theory makes more sense.

The line of tourists moves slowly upwards through the castle, giving me plenty of time to soak up its ambiance. The wood floors and decorations have long since disappeared, leaving the stone walls and an occasional information sign behind.

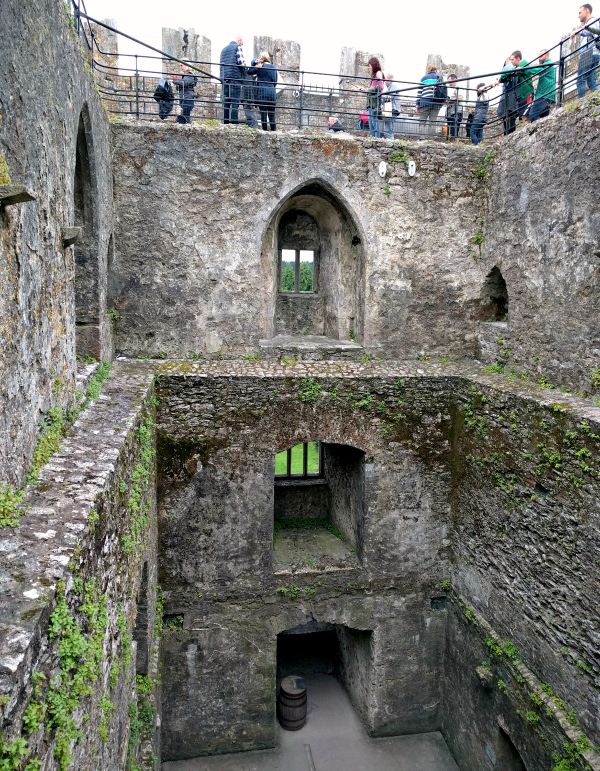

We enter through the basement, underneath the Great Hall. Since there are no ceilings or floors, it feels as if we’re entering the great hall itself. The central space goes up several stories, and it’s obvious that the tower was built around a central hall.

It’s difficult to imagine that we’re in the basement, until I get further into the room. There are fireplaces in the walls, close to where the floor of the Great Hall would have been. Without the floor, they appear to be suspended at random intervals in the stonework.

I pass through the family room, located above the Great Hall,

And several side chambers, including the little garderobe

and the Earl’s bedchamber.

The ambiance of these rooms are difficult to capture in pictures. There’s nothing left but the stone walls and open windows. Yet there’s an definite mood to the place: stark, gritty, real. In some ways Blarney Castle feels more alive because it doesn’t have all the trappings of civilization. It leaves the imagination free to fill in the gaps – with some help from the information signs, of course.

Finally the winding tour of the castle ends at the Banqueting Hall, the last room connected to the central staircase. From here I can look down the central hall of the tower, down past the banqueting hall to the family room and great hall I passed through not long ago.

And from here, an even narrower curving stone staircase leads to the ramparts – and the Blarney Stone.

Crane your neck back,

look up the castle wall,

which almost touches the sky

to see the platform there.

Your heart skips a beat,

when you see the narrow stairs.

Fingers crossed you begin your accent

up the narrow curving stairwell,

to the top of the castle wall.

The breeze ruffles your hair,

as you walk slowly around the fortifications there.

The worst is yet to come,

coat off, lay on your back,

to do the daftest thing of all.

You lean back through the narrow gap,

bend your head backwards,

and kiss a stone in the castle wall.

~ “Kissing the Blarney Stone” by David Harris

No one seems to know just where the Blarney Stone came from, or when people started visiting the castle just to kiss it.

One legend says that the stone is Jacob’s pillow, brought to Ireland by Jeremiah the prophet and used as the “Lia Fail,” the stone on which the High Kings of Ireland were crowned. Another legend says that the stone is the Stone of Ezel, which David hid behind while he was fleeing King Solomon, and was brought to Ireland during the Crusades. A third legend believes that it was the coronation stone of Scottish kings, and that St. Columba used it as a traveling alter in Scotland. He brought the stone to Ireland, where it became the “Lia Fail.”

The legend I hear most often is that Cormac MacCarthy, King of Munster, sent 4,000 of his own men to aid Robert the Bruce in his now-legendary defeat of the English at Bannockburn in 1314. Robert the Bruce split the Scottish Stone of Destiny in half, keeping half for the Scots and sending the other half to Blarney Castle, Cormac MacCarthy’s principle seat. A century later, King Dermot McCarthy used that same stone when he built his new castle.

Just as there’s no consensus on where the stone came from, there’s no clear origin story for why kissing the stone would give one the gift of eloquence. The only story I can find is a quick two-liner about a witch who was saved from drowning by a King of Munster. In gratitude, she gave him a spell which, if he kissed a stone at the top of the castle, would give him the ability to speak well and win people to his side.

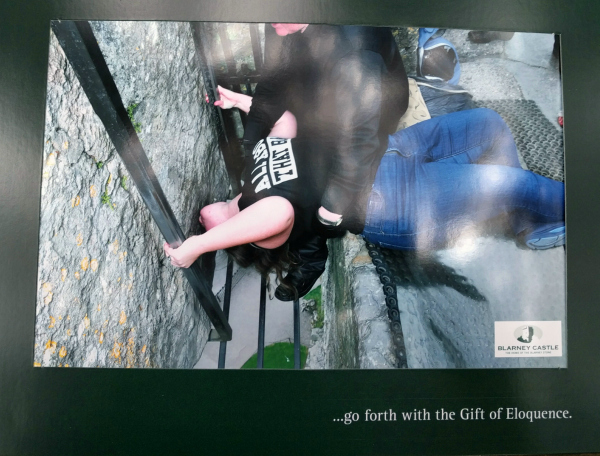

To kiss the stone, one lays down on the flagstones, grips the bars on the stone with both hands, and allows the man on duty to support your upper body as you lean backwards to kiss the stone.

I am not at all sure I want to do this, but talking with the folks in line behind me helps keep the fears of plunging to my death at bay. This is their third trip to kiss the Blarney Stone!

“Just don’t think about it,” I tell myself as I take off my glasses, empty my pockets, and place my bag off to the side. A deep breath, steady hands under my shoulders, cold iron gripped in my hands, and a quick brush of lips against a rough stone surface, and it’s over.

My hands are shaking as I put my glasses back on and collect my bag. I cannot tell if it’s fear or exhilaration or excitement or all three. But I did it! I kissed the Blarney Stone.

I lean against the parapet, enjoying the solid feel of the stone under my fingers and against my legs. The views from the ramparts are absolutely gorgeous:

Looking North towards Blarney Village

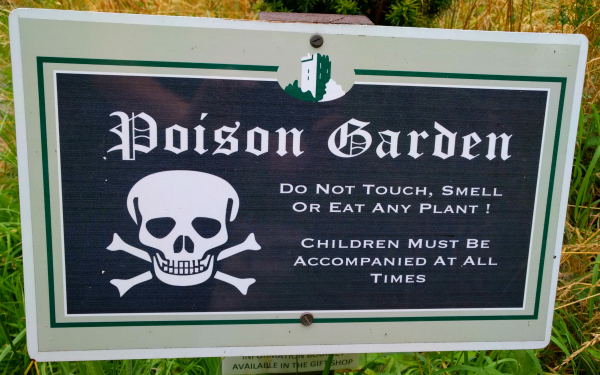

Looking down on the Poison Garden

Looking east over The Court, Lookout Tower, and estate grounds

Descending through the castle tower takes little time at all. There’s not much to see on the return trip, as if the tour designers are aware that nothing can top the experience of kissing the stone.

Back on ground level, I follow the steps past the oubliette and down into the courtyard of the demolished Gothic mansion. Here are the detailed information signs about the history of the castle, its owners, and of course the stone itself.

The castle is a traditional fortified tower house, built in the 1480s on the site of an earlier stone building. The limestone cliff it’s built on served as the quarry for the building, which is why the north wall seems to be an extension of the cliff itself.

It was a principle seat for the MacCarthy Gaelic lords for about 200 years, until they sided with the Jacobites and the Crown in the wars in the late 1600s. It was finally taken away from the McCarthy family in 1691 and sold a couple of times before the Jefferys bought it in 1703. They married into the Colthurst families, and their descendants still own the property today.

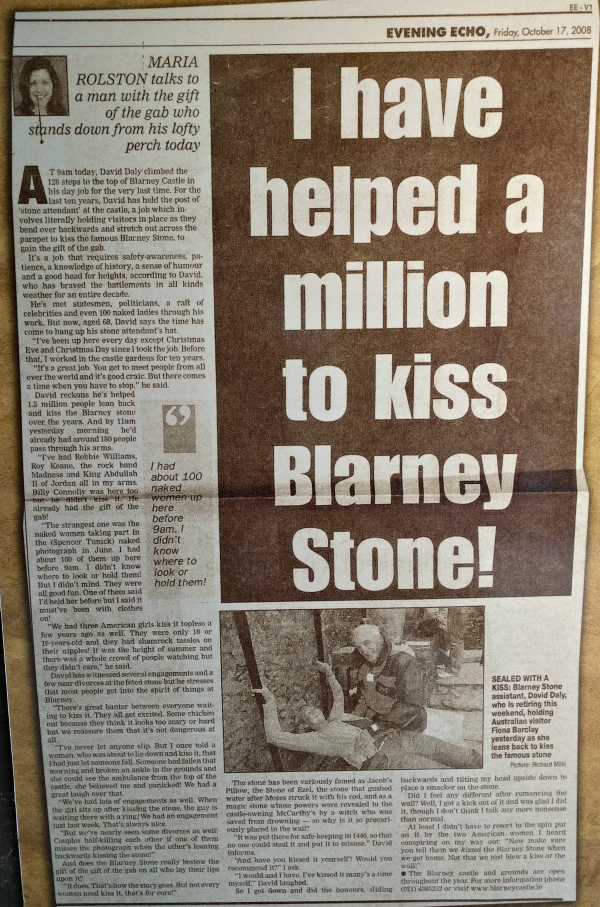

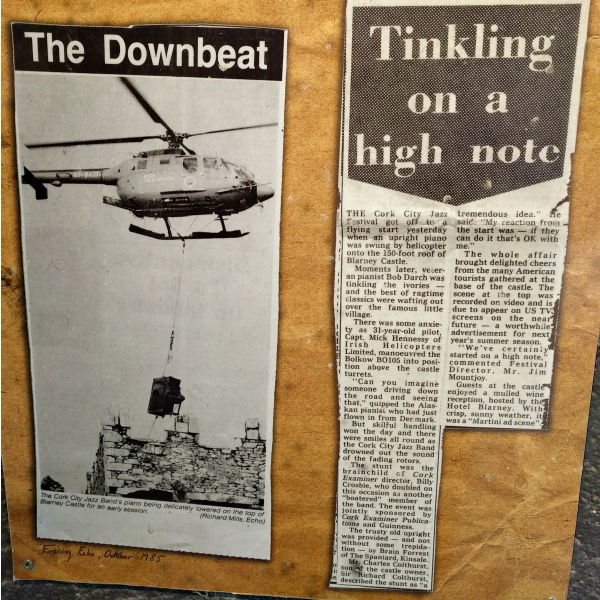

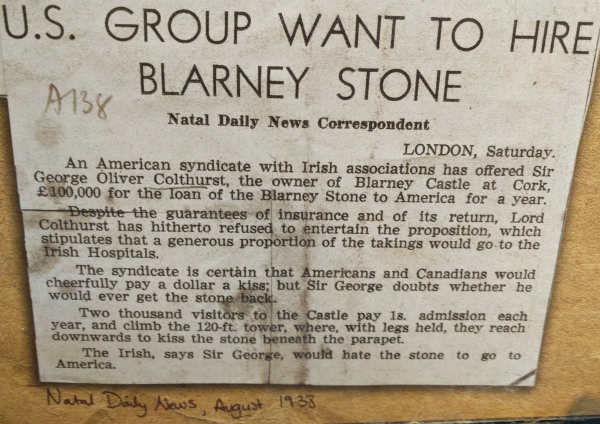

What I find most intriguing about the information on display are the press clippings about the stone itself.

Then there’s this article, which makes me smile every time I read it.

Before I leave the Castle to explore the estate grounds, I take in two more interesting factoids about the castle and its stone.

The first is that no one seems to know exactly what kissing the stone will do! Some say it gives you the gift of eloquence, others that it gives you the ability to be persuasive, and still others say it’s the ability to sound good while talking a load of crap.

And the second thing I find out is that the term “Blarney” entered the English language in the 1600s. According to the sign:

In 1601, he [Cormac mac Diarmada McCarthy, Gaelic Lord of Blarney] wrote a letter to one of Queen Elizabeth’s advisors demonstrating his loyalty with an account of how he had refused to join the rebel forces and had lost many of his gentlemen and followers in the service of the Crown. Yet, a few months later, Cormac’s men had reportedly joined the rebellion [against Queen Elizabeth I]. The legend goes that Queen Elizabeth I was so annoyed by his ambiguous communications that she remarked “it was all Blarney.”

Satisfied that I’ve learned everything I can about Blarney Castle and the Blarney Stone, I set off to explore the extensive estate grounds. There’s a lot to choose from: the poison garden, the rock close, Blarney House, a wilderness walk.

I start with the Rock Close & Water Garden. It’s a gorgeous 18th century grotto just opposite the road from the castle grounds. Intriguing rock pathways twist and turn across the garden slope, leading down to the waterfall,

past plants as tall as I am,

to the Druid’s Cave.

Behind the Druid’s Cave are the “Wishing Steps,” a set of narrow stones cut through the rock to reach the top of the waterfall. Legend says that if you walk down the steps backwards with your eyes closed, your wishes will come true.

A series of living tunnels leads me out of the Rock Close

And back in again. I climb through the dolmen, said to be the entrance to a megalithic tomb,

and continue up the path to the Witch’s Kitchen.

The Witch’s Kitchen is a single-file entrance to a small cave in the bank of a hill. It’s been rocked over to appear as a rough stone hut. I would guess it’s a folly, built as part of the garden, but it is memorable.

I take a quick walk through the Pinetum (an arboretum specifically for pine trees), then re-cross the street and head towards the Poison Garden.

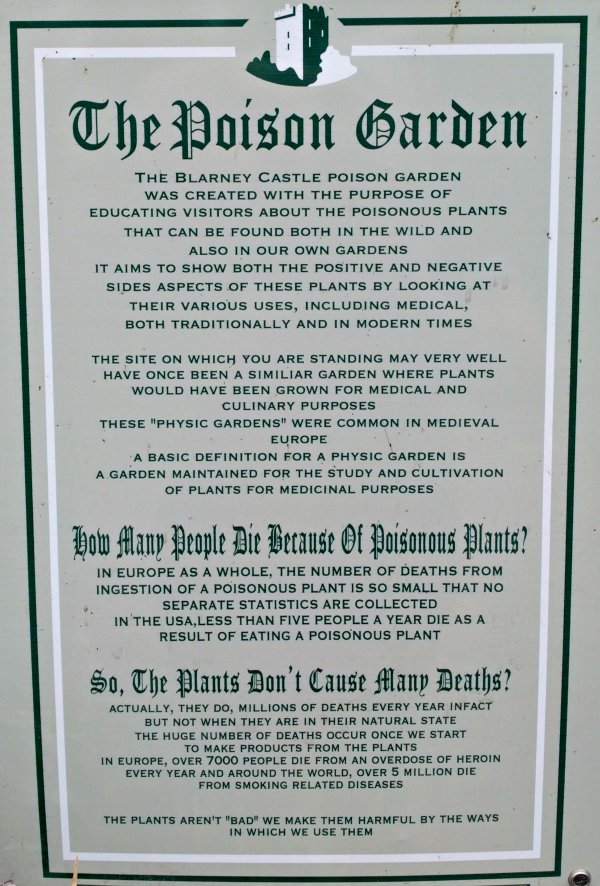

Billed as Ireland’s only poison garden, the Poison Garden is nestled against the castle battlements.

Some combination of the sign, the grey afternoon, and the garden makes me feel like I’m walking through a witch’s garden. And when I find both a mandrake

And wolfsbane,

I feel as if I’ve slipped into a Harry Potter novel. It’s difficult to resist the urge to pull the mandrake right out of the soil, to see what its roots look like.

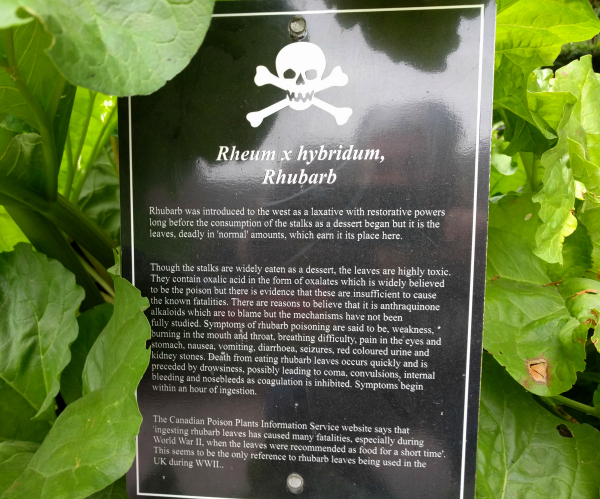

Next to a common juniper, I’m surprised to discover that rhubarb is a poisonous plant. Apparently the stalks were used as laxatives before we began including them in desserts. But the leaves are deadly:

I’ve clearly been watching too many crime shows, because I can easily imagine half a dozen scenarios in which a modern murder is committed by rhubarb poisoning. It would be the perfect crime, with an untraceable murder weapon.

A path leads west from the poison garden into the main grounds of the estate. I pass another lookout tower

But it’s the tree next to the tower that’s really something.

A bit further on is another remarkable tree, this one a Thuja plicata, more commonly known as a Western Red Cedar.

Each of its main limbs is easily twice as thick as I am. They’re tall too – even the adults have to jump up onto the limbs for a photo opportunity.

From here, the path splits. I follow the left fork through a sweeping open lawn, a small forest on one side and an arboretum on the other. There’s a few people walking near me, and when we round the corner we all stop and stare.

This is Blarney House, built in 1874 in the Scottish Baronial style.

Unlike Blarney Castle, which is all intimidation and raw power, the manor house is a true estate house, with turrets, towers, and interesting architecture at every turn.

Home of Sir Charles Colthurst, Baronet, the house is open for tours from 10 am to 2 pm in the summer. Since it’s now after 6:00 pm, the doors stay firmly shut.

What a shame – if the inside is as fantastic as the outside, that would be a tour worth taking!

Several walking trails start at or near Blarney House. It’s too late to head out to the lake, but I do have time to explore the old limekiln and the fern garden.

The old limekiln is much prettier than I expect – more of an overgrown tower melted into the local landscape than a hive of industry.

The fern garden is just as lovely as I expect it to be. A shallow stream runs through a gully, and the smell of dampness and ferns and forest reminds me of home.

The most spectacular feature is the waterfall, which I stumble across quite unexpectedly.

I stand for a few minutes, listening to the trickle of falling water and the stillness of the forest. If I lived here, I would come hear often just to breathe in the sounds of nature.

It has been an unexpected yet fabulous afternoon. I had not expected Blarney Castle to be so full of nature – the rock close, the pinetum, this fabulous fern garden, the steady flow of the Blarney and Martin rivers. Nor did I expect the castle to be so captivating, or that the estate grounds would host the sort of mansion house I would love to live in.

My only regret is that I can’t spend more time walking the paths to the ends of the estate and exploring the lake. But there’s always next time . . .

Up next: Dublin Revisited – Exploring Maynooth Castle

Leave a Reply