July 27, 2016

It is a typical overcast Irish morning as you cross the border from the Republic of Ireland into Northern Ireland. The express bus is moderately full but quiet as it speeds along the motorway, the scenery mostly trees and traffic. You’ve been up since early this morning, and with nothing to hold your attention you slide into sleep.

When you awake, the weather has changed completely. Instead of clouds and an ominous feel of rain, the sky is deep blue with wispy white clouds. It’s a good omen for your first visit to Northern Ireland.

Fifteen minutes later, you’re standing on a busy, narrow street in the heart of Belfast. Quickly you review your itinerary: St. George’s Market, a City Hall tour at 2:00 pm, a guided tour of the Crumlin Road Gaol at 4:00 pm, and a visit to the Peace Wall before heading to your hostel.

As you set off for St. George’s Market, you smile. It’s mid-morning, and the exhilaration of exploring a new city and of being on holiday while everyone else is working rushes through you.

When you arrive at the market, it’s not quite what you expect. The building is a huge warehouse, done up in brick with fancy modern signage.

The market is entirely enclosed, with a roof overhead and long lines of vendors filling the interior. A Friday market has been held here since 1604, but this new enclosed marketing building was constructed at the end of the 19th century and refurbished in 1997.

You wander slowly up and down the aisles. There are all kinds of things for sale: baby clothes, books, fresh produce, T-shirts, CDs, fresh fish, fudge, ready to eat meals, Lego sculptures. It’s a strange mix of farmer’s market and home bargain buys.

One of the bargain stalls sells UK to US adapters for 3£ each. You’ve been looking for just such an adapter ever since your fancy one broke last week. Another stall nearby sells the best salted caramel fudge you’ve ever tasted. And a third stall halfway down the farmer’s market row sells you a hot bowl of Irish stew, which is both breakfast and lunch.

When you emerge into the sunshine, the pull of the nearby river is too strong to resist. You have plenty of time to make your way to City Hall, so you walk the couple of blocks to the River Lagan.

Oddly enough, although the River Lagan is a key waterway in Belfast today, it’s not where Belfast gets its name. Belfast is an Anglicization of Béal Feirste, meaning “river mouth of the sandbar.” The original settlement was built around a sandbar formed where the Farset River joined the Lagan. Today the Farset river runs underneath Belfast, but the River Lagan is still a mighty presence.

As you follow the river walk north along the western bank, a statue appears before you.

She is Thanksgiving Square Belfast. According to a nearby information sign, she “represents various allegorical themes associated with hope and aspiration, peace and reconciliation and is derived from images from Classical and Celtic mythology. Her position on the globe signifies a unified approach to life on this earth. It encompasses oneness, while celebrating the diversity of culture that exists in our global village.”

You pass the Laganside Courts and the Northern Ireland Court Service before arriving at Lagan Weir. Here a pedestrian-only footbridge spans the River Lagan, along with a truly ostentatious statue called Bigfish.

What really captures your attention, though, is the imposing Customs House.

Staring at the imposing presence, it’s easy to wipe away the modern bridges and buildings and instead imagine a river bristling with ships of all kinds, waiting to have their cargo expected and approved by a small army of customs house officials.

The back side of the building gives onto a huge courtyard, with imposing flights of stairs leading up to a main entrance. You’d like to get a closer look at this High Italian Renaissance building, but the courtyard is off limits to all but staff today.

With reluctance, you turn away from the customs house and the river to follow Queen’s Square back to the heart of Old Town.

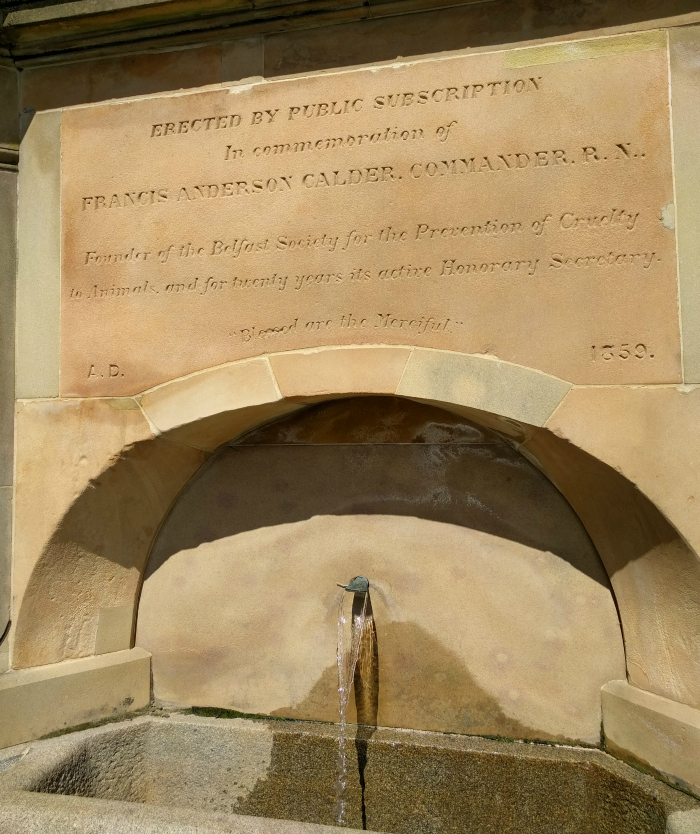

You pass this memorial fountain to the founder of the Belfast Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

A few minutes later, your eye is caught and captured by the Albert Memorial Clock.

At first you are drawn to the height of the tower and the way the yellow sandstone catches the afternoon sun.

When you walk closer, you begin to notice individual components of the tower.

It’s a marvelous piece of engineering, hugely heavy with a 2 ton bell inside. In fact, the building is so heavy it leans on its foundations. It was built in the 1860s in honor of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, and underwent a major restoration project in 2002 to shore up the tower foundations and to clean the entire tower. It’s also said that one young lad actually scaled the tower in 1912 to get a better view of the launch of the Titanic!

You pass St. George’s church, built on the site of the original settlement over 1,000 years ago . . .

. . . a strikingly handsome apartment building . . .

. . . and very modern alley.

Finally, you turn onto Donegall Place and there, framed by the buildings on either side, is Belfast City Hall.

Surrounded by a tasteful black picket fence, the grounds are teaming with tourists and Belfast natives enjoying a late lunch. City Hall is massive – it encompasses an entire city block, the white Portland stone gleaming in the afternoon light.

Several statues and memorials dot the grounds, including a tribute to the Belfast lives lost on the Titanic:

The inscription reads: “Erected to the imperishable memory of those gallant Belfast men whose names are here inscribed and who lost their lives on the 15th April, 1912, by the foundering of the Belfast-built R.M.S. Titanic, through collision with an iceberg, on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York.”

The main tourist entrance is all pillars and fussy embellishments.

Inside, the foyer is spacious and full of light. The black and white marble squares beneath your feet feel utilitarian. Their real purpose, however, is to set off the Grand Staircase in front of you.

Long hallways stretch away on either side of the foyer. They contain several gorgeous stain glass windows, each with their own story.

Spanish Civil War Window

From the plaque: With the agreement of all political parties, this window was commissioned to reflect the contribution of citizens from Belfast to the fight against fascism in the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939.

About 320 Irish volunteers fought against Franco’s forces as members of the XV International Brigade. Of these, 48 were born in Belfast and 12 died in Spain.

For many, the Spanish Civil War became an opportunity to stand against the growth of fascism. Men and women from all over the world answered the call to defend democracy and their working class counterparts.

Northern Ireland, already impacted by political and religious divisions, was deeply affected by these events and many local people took part in the Spanish Aid Campaign, including Belfast activists Alderman Harry Midgley, Betty Sinclair, Sam Haslett and Sadie Menzies. They played a significant role at home, raising awareness to support the democratic cause abroad.

This window was designed, manufactured and installed by Alpha Stained Glass. The design incorporates a poem written specially by Sam Burnside MBE.

Having given all they had to give,

To save from blood and fire and dust

At least a hope that we can trust.

We must remember them – and live.

(Extract from “The dead have no regrets” by Aileen Palmer; 1939)

“No Pasarán.”

—

Pathways Memorial Window

From the plaque: This window is dedicated to the memory of all those whose organs and tissues were retained without the knowledge or consent of relatives and families following post mortem examinations in former times.

The outline of a mountain peak and converging pathways speak of a hardship shared by all those who mourn while leaves fall silently from the trees as tears. A red ribbon binds all together in passion and pain.

But the rising sun promises a new dawn, and hope is symbolized by doves ascending and a butterfly spreading its wings in anticipation of flight.

United in the light of remembrance, both candles and a multitude of stars preserve the memory of the many loved ones commemorated by this window.

—

The Dockers’ Strike Centenary Window 1907

From the plaque: This window was commissioned to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Dockers’ Strike of 1907, a significant event in Belfast’s history. Dockworkers, led by “Big Jim Larkin” went on strike to campaign for the rights of working class people and secure the right to organize their own trade union, the National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL).

All sides of the working class community, including dockers, carters, coal heavers, boilermakers and tobacco workers, united in support and came out on strike. Thousands thronged to Custom House Square to hear the speeches of the strike leaders, especially Larkin, noted for his eloquence and energy.

The uniqueness of the solidarity of the strike was evident by the fact that the Independent Orange Order collected donations for the strikers on 12 July 1907. There was a mutiny within the ranks of the Royal Irish Constabulary and the city was brought to a virtual standstill.

James Larkin, from Liverpool, whose silhouette is in the center of the window, used the phrase “One Big Union” (OBU) to signify unity. He led the way for the establishment of the city’s trade union movement.

—

Belfast City Hall Centenary Window

From the plaque: This window celebrates the many successes and achievements witnessed by City Hall during the last 100 years and is a symbol of hope and inspiration for the future.

The work recognizes the contributions to the city made by the linen, shipbuilding, aircraft and rope making industries, and celebrates Belfast’s achievements in terms of science, technology, sport, music, literature, art and theatre.

The tree with the rising sun behind it symbolizes hope, strength, growth, regeneration, and reconciliation. “The leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations.” Rev. 2:22.

The leaves are multicolored symbolizing the many varied cultures and traditions within the city. The 100 tiny lights are a symbol of hope for the next 100 years.

—

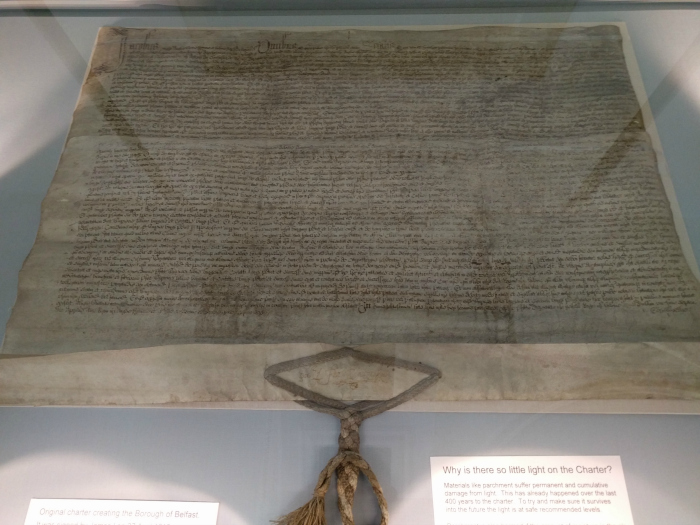

Back in the foyer, you inspect the glass case to the right of the main doors. It contains the original 1613 charter that elevated Belfast from a community to a Town with its own royally appointed government.

Quite a few people are milling about, waiting for the tour to begin. Just as our guide steps out from behind the reception desk, a wedding party hastily makes their way through the crowd.

As the clock strikes 2:00 pm, George introduces himself as our guide for the next 45 minutes. He explains that the building we’re about to explore stands on the site of the White Linen Hall. When Queen Victoria elevated Belfast to a City in 1888, the Belfast Council decided that the Town Hall no longer reflected the city’s status.

They purchased the White Linen Hall property, devoted two years’ profits from the city gas works to fund it, and started importing Carrara, Pavonazzo, and Brescia marble from Italy, as well as a fourth type of marble from Greece.

As we ascend the marble staircase, you feel as if you’re in a castle instead of a government building. The red carpet actually sinks beneath your feet, and is so thick you couldn’t make a noise even if you tried.

You pause on the landing, looking up to the rotunda

And down at the Belfast coat of arms beneath your feet.

The Latin motto pro tanto quid retribuamus literally translates to “For so much what shall we repay?”

When you reach the rotunda, George (your tour guide) is explaining the paintings that stretch around the base of the dome. Your attention is drawn to something else: a small display showcasing various Keys to the City.

From the Rotunda, we enter the Council Chambers, where the Belfast Council comes together on the first working day of every month. Like most British-inspired chambers, the room is separated into two banks of seats facing each other with a long row of tables down the middle and a spectators’ gallery above.

At your guide’s urging, you try out the Lord Mayor’s chair while he explains more about who sits where, how the council works, and a bit about the previous Lord Mayors.

You listen to your guide with half an ear, and with the other half you chat with the woman who took your picture. She and her husband are visiting from Australia, and their nephew has organized this tour to City Hall.

From the Council Chambers we pass into the Reception Hall, which houses various gifts presented to the city over the years.

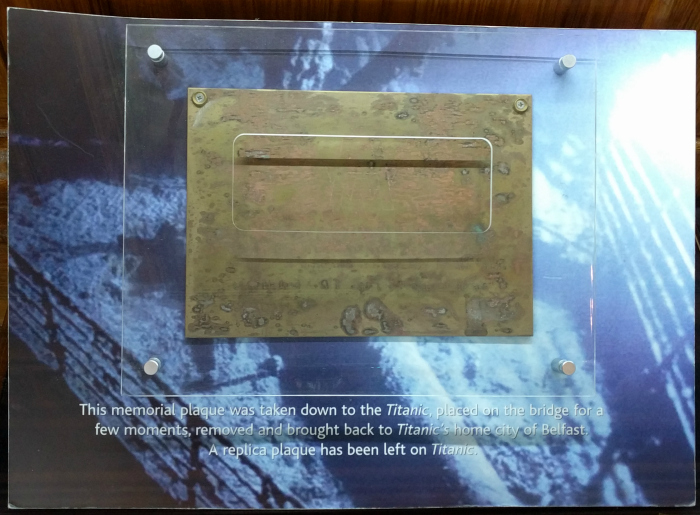

One in particular catches your attention:

The inscription reads “This memorial plaque was taken down to the Titanic, placed on the bridge for a few minutes, removed and brought back to Titanic’s home city of Belfast. A replica plaque has been left on Titanic.”

The last stop on your tour is the Great Hall. It’s being set for an upcoming banquet, and the height and elegance of the room makes you wish for an invitation.

The only damage done to City Hall in World War II happened in this room. Luckily, the stained glass windows had been removed at the start of the war, and the structural damage was easily repaired.

Three of the seven windows commemorate the only three British monarchs who to visit the city of Belfast. The remaining four windows depict the four provinces of Ireland: Ulster, Munster, Leinster, and Connacht.

Heading spinning from the grandeur and history of City Hall, you thank your guide and descend a much less fancy staircase to a side entrance. Your decision to take a tour of City Hall was something of a gamble, but the last 50 minutes have really opened your eyes to the wealth and opulence that flowed through Belfast a hundred years ago.

It’s difficult to believe that your day is only half over. As you set off towards west Dublin and the Crumlin Road Gaol, you wonder what other surprises the afternoon will bring.

Up next: first impressions of Belfast, part 2: Civil War.

A nice tour, told in 2nd person for a change-of-pace, from “Hula-hoop girl” (Thanksgiving square) to Belfast heraldry — I note that the “doggy” is chained to the crown…

In a compare/contrast probably more appropriate with your next edition, Belfast vs. Dublin, the cities, the architecture, the people & their attitudes, and the lives of the more “normal citizens” (beyond the opulence)?