June 6, 2016

It’s a hot 11:00 am here in Puerto Ayora. My friend and I have just finished moving into the second of our two Galapagos houses. This one is on the very west side of town, two blocks from the main street. We’ve definitely moved out of tourist-ville and into the heart of “real” Puerto Ayora.

Two workers are building a new cement wall to separate our house from the one next door, and their voices filter in as we explore our new home. It has some advantages over its predecessor (two ensuite rooms downstairs, a more affordable price, much closer to grocery stores) and some disadvantages (super slow internet, no hammock, limited living room space).

Satisfied that we’ve unpacked as much as we’re able, we set off on our afternoon adventure: exploring the Charles Darwin Research Station. The Charles Darwin Foundation works with the government of Ecuador and the Galapagos National Park Directorate to “provide scientific knowledge and assistance to ensure the conservation of Galapagos.”

The station is listed as one of the top tourist destinations for Puerto Ayora, and many cruise ships bring their groups through as well. There’s a small exhibition hall, but the real draw is to see the famous Galapagos land tortoises that are part of the station’s breeding program. There’s also a land iguana breeding program. After days of admiring the marine iguanas, I’m curious to see what their land cousins look like.

Getting to the station involves a long, hot walk across town. The back of my neck is badly burned from our weekend adventures. I slather it in sunscreen before leaving the house, but even so the hot sun feels like it’s penetrating deep into my skin. To compensate, I do something I’ve never done before: I use my red umbrella as a parasol. Definitely not the classiest look, but hey – it works!

When we arrive at the Charles Darwin Research Station, it’s just after 1:00 pm. There’s no one around, and soon we find out why: the exhibit hall (and bathrooms) close from 12:30 – 2:30 pm for lunch. We’re too hot and sweaty to wander away, so we find ourselves a lovely table on their shaded back patio and wile away an hour until the doors open at 2:30.

Once inside, the first thing you see are a giant whale skeleton and a land tortoise statue.

I marvel at the side of the tortoise – the top of the shell comes up to my knees, at least, and the size of it is much bigger than I had imagined.

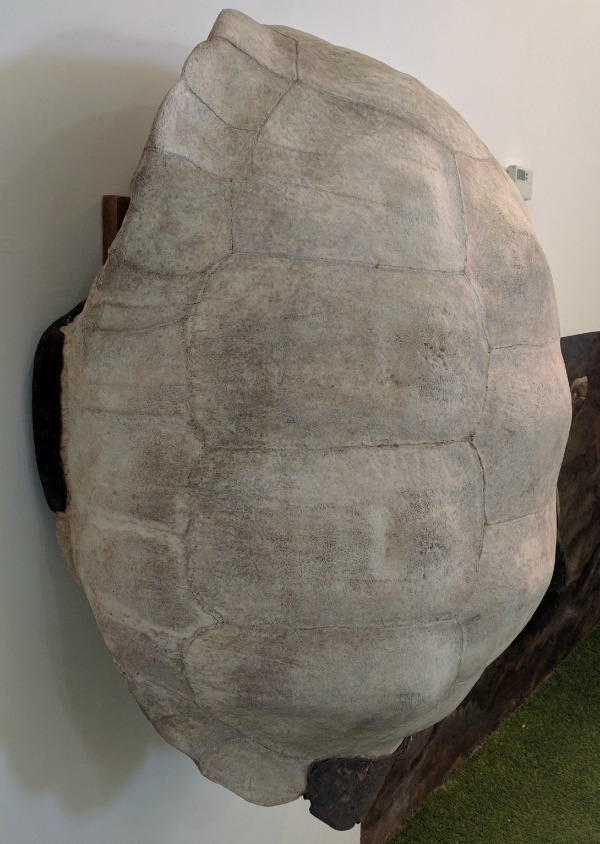

I’m also captivated by the shell casting attached to the wall.

With the right angle, you can see inside the casting. There’s a lot of space inside! It’s almost big enough to image sitting in it and using it for a small boat. Imagine what it must look like full of tortoise!

The exhibit hall is not very big, and it takes no time at all to cruise through the rest of the exhibit. My eye is drawn to a very colorful representation of the Galapagos Islands . . .

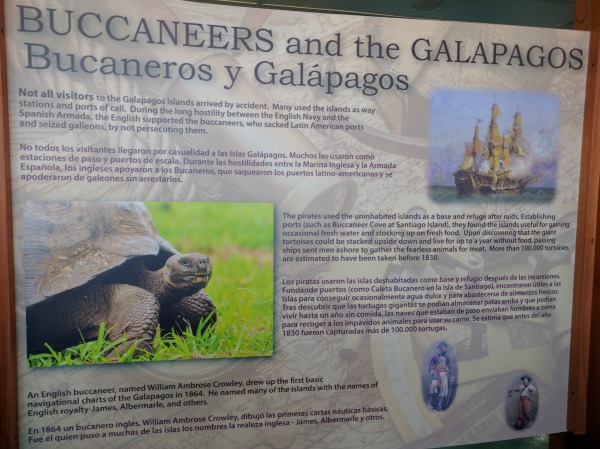

. . . and by a signboard called “Buccaneers and the Galapagos.”

From this sign and others, I learn that the Galapagos were uninhabited through most of the early 1800s except for a small quinine farming operation on one of the smaller islands. They made a good stopping place for pirates and whalers, who sometimes found fresh water, but mostly stopped for the giant tortoises.

The buccaneers discovered that they could stack live tortoises upside down on their ships, and that the tortoises would live for up to a year without water. It’s hard to get accurate numbers, but best guess is that over 100,000 Galapagos land tortoises ended up as pirate soup in the early 1800s.

Surprisingly, I also learn that although Darwin visited the islands in the 1830s, the first basic navigational charts weren’t made until 1864 by a buccaneer named William Ambrose Crowley. Being English, he gave most of the islands English royalty names like James and Albermarle. It’s unclear from the signboard how many of those English names survive today.

Now that I know all about the tortoises and their pirate history, I’m ready to see one. We leave the air-conditioned exhibit hall and take a dusty path curving away from the hall. We’re treated to a display of why the mangrove finch is critically endangered, and then suddenly the path is running along a fenced enclosure, and there before our eyes is the famous Galapagos giant land tortoise.

As our eyes become accustomed to shape of their shells, we find more and more turtles sleeping in the afternoon shade.

There are numbers painted on the backs of their shells, mostly in the 20s. There are no signs to explain what we’re seeing, or how many breeding pairs there might be. Luckily, there’s a tour group ahead of us, and we eavesdrop on his presentation.

The Galapagos tortoise is the largest living species of tortoise, and is only found here in the Galapagos. (The only other giant tortoise species exists on an island several hundred miles east of Tanzania.) They can live over 100 years (longer sometimes in captivity), and can grow up to 900 pounds.

By the 1970s, there were maybe 3,000 tortoises left. That’s when conversation efforts began, including the breeding program at the station. When tortoises mate, the female digs a hole in the sand, drops her eggs (up to 16), covers them, and leaves them to incubate. When the baby turtles hatch four to six months later, they’re cared for by station personnel for 3 to 5 years, until they have a good chance of surviving when released back into the wild.

The guide we’ve been eves-dropping on also introduces his group to Diego, the program’s star tortoise. For a long time the local rock star was Lonesome George, so named because he was the last of his species.

They tried to get Lonesome George to mate with other species, but it never worked and in 2012 Lonesome George’s species went extinct. In a place that is big on preservation and conservation, I am intrigued by the guide’s offhand comment that they considered artificial insemination and rejected it.

There are three tortoise enclosures in all, and we move around them, taking in the different turtles. I finally get a good shot of one out in the sun . . .

. . . and a completely adorable picture of two tortoises going nose to nose.

Further research for this post reveals that these are most likely both males, and that they establish dominance by who has the longest neck.

We’re also treated to the sight and sound of a pair of breeding tortoises at the far end of one enclosure. According to research I did later, mating is one of the few times that tortoises make any noise at all. The tortoises mate year round, so I guess we were lucky to witness this particular aspect of tortoise life.

In between the tortoise pens is a series of three smaller enclosures for the land iguanas. Only one enclosure is inhabited, and he or she seems quite friendly. It comes up very close to the wall, much to my delight.

Here there are a couple of signs, but none that tell us what we really want to know. How long do they live? How many eggs do they lay? Is there a way to tell if an iguana is a boy or a girl?

Once again, the tour guide is ahead of us, standing by the enclosure answering questions from a couple group members. Land iguanas live 50 or 60 years, grow three to five feet in length, and weigh up to 25 pounds.

According to the tour guide, the one we’re looking at is a male, and an older one at that. The guide doesn’t answer my question about how he knows its gender, but he does say that you can tell the age of an iguana by the variety of coloration on its skin. The more colors and variety, the older it is.

We linger at the land iguana enclosure for a few minutes, taking in the spikes along its spine and on its forehead, and the yellow and brown colorations of its skin. I prefer the marine iguanas with their black skin, but I have to admit that the yellow coloration is intriguing in its own way. There’s also a pink species of iguana on another island; I doubt we’ll get to see it, but I do see a picture in the exhibit hall.

On our way back to the station, we also pause for a few minutes to watch Diego eat an afternoon snack. They are big and impressive, these land tortoises, but other than their size they don’t really do much for me. I much prefer the marine iguanas.

It’s just after 4:00 pm when we leave the Charles Darwin Research Station. We don’t go far – our favorite rocky beach is only five minutes’ walk down the path. I settle in to read and write some post cards, while Maureen goes for an afternoon swim.

It’s a wonderful way to end our weekend of exploring. Tomorrow, Wednesday and Thursday are work days. We have a plan for places to explore in the afternoons, but I am also looking forward to a quiet day of downtime tomorrow to work and let the experiences of the weekend settle in.

Leave a Reply