July 27, 2016

You’ve been walking for 30 minutes on this beautiful July afternoon, and already you feel a world away from the heart of Belfast.

You’ve definitely entered suburbia. The traffic hurries from place to place, and hair salons, computer repair stores, and betting parlors line the streets alongside gas stations and apartment buildings.

When you see the Crumlin Road Gaol for the first time, it’s something of a shock.

If you’d thought about it, you’d have expected the Crum to look and feel modern, utilitarian, functional. The Crum is all of those things, but there’s also a strong feeling of public grandeur.

Across from the Crum on your side of the street is another building that might have been a public building. Now it’s a gutted ruin, grass and weeds growing over the grounds, windows without glass, graffiti and who knows what else on the walls, all protected by a picket fence that has clearly seen better days. It certainly adds to the atmosphere of the neighborhood, but probably not in the way the tourist board intended!

You’ve pre-booked your ticket for the 4 pm tour. After swearing at your fancy Google phone for a few minutes, it finally connects to the cell network long enough to pull up your booking confirmation.

Through the main gates, the Governor’s Mansion fills your view. You expect the jail to feel utilitarian. But the decorative quoins on the corners and the fancy bricks around the windows brighten up the building and give it a bit of character.

Throughout its 150 year history, the Crum (officially known as the HMP Belfast) had 26 governors. They are recorded on a scroll outside the Governor’s Office.

Many governors served for as little as a year or two, while the longest terms of service are rarely more than 5 or 6 years. Since most of these governors were required to live on site with their families, it’s hardly surprising that their tours of duty were short.

The tour officially begins in the gaol’s basement, which is also home to Cuff’s Bar & Grill and a small museum. Built in 1843-1846, the Crum was designed by Sir Charles Lanyon. It’s built of black basalt rock and modeled on Pentonville prison in England. It was designed to hold 500 to 550 prisoners, one to a cell. (Apparently that was a new-fangled notion in Ireland in the 1840s.)

When the prison opened in 1846, the cells pretty fancy: a water closet, a fixed basin, and a gas light, along with a hammock, a stool, comb, brush, towel and soap.

Sometime after 1847 the prison authorities got tired of unblocking the pipes running into the cells (it happened frequently) and removed the water closets and basins. The inmates were given chamber pots for their cells, which they had to “slop out” each morning until the day the prison closed in 1996.

Can you imagine being sentenced to jail in 1996 and having to use a chamber pot while locked in your cell overnight? And – even more gross – having to empty it each morning?

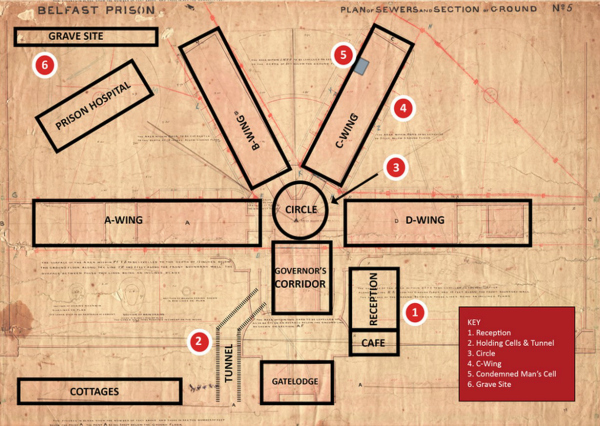

The prison grounds itself are a pentagon, with one edge facing the road. The base of the prison is a central courtyard with the four wings radiating from it.

Photo Credit: www.crumlinroadgaol.com

You finish your museum tour just as Charlotte, your official tour guide, herds everyone into a small meeting room. Charlotte is clearly fascinated by the history of the gaol and is eager to show you around.

Your first stop is the reception room. Here a new inmate was shown to a cubicle, told to strip and shower, and place any personal effects in the pouch on the door. The pouch would be locked away for safe keeping until their release.

Standing in the middle of the reception room, bare of everything except a red and black tiled floor and the wooden cubicles, it’s almost impossible to imagine that this room was in operation a mere 10 years ago.

It feels like the bathrooms at the summer camps you attended as a kid: bare, functional, smelling of damp, and not someplace you’d want to spend any time at all.

After the reception hall, you double back into the main part of the gaol and follow a set of stairs down to The Tunnel.

After the Crum was opened in 1846, the powers that be decided that having the new Crumlin Road Courthouse just across the street was a brilliant idea. Having worked with Sir Charles Lanyon on the design of the Crum, they naturally hired him to build the courthouse too.

There was only one problem: transferring people from the gaol to the courthouse and back again in full view of the public was asking for trouble. So they decided to build a tunnel under Crumlin Road to connect the two buildings.

The tunnel opened in 1850, the same year as the courthouse across the street. It’s 82 meters long and lined on one side with the hot water pipes used to heat the buildings.

The tunnel was reinforced with concrete sometime in the early 20th century to account for the transition from horse and carriage to cars (the tunnel roof tunnel is only a few feet below the road’s surface).

The tunnel is cool and damp as you walk to the far end. There’s no sense of claustrophobia, but you imagine it would be a different story full of wardens and prisoners and hotter than Hades with the heat of the pipes.

Patrick Greg, a former prison officer who served in the Crum in the early 1980s, wrote:

“I hated . . . the hustle and bustle of the holding area below the Crumlin Road Courthouse. Most of all, I hated the tunnel. . . . There was barely enough room for two people to walk side by side, which was exactly what you had to do when handcuffed to a prisoner due for court. It was unbearably humid, and just small enough to make me edgy and slightly claustrophobic.” [The Crum, 2013 edition, pg. 213]

At the end of a tunnel a rusted out door leads to the bowels of the Crumlin Road Courthouse.

Prisoners were held in the Crum or in the courthouse basement until it was their turn to appear in court.

Patrick Greg writes: “The stairs up to the dock in number 1 court were steep and narrow. You almost had to take side steps when negotiating them, and on each tread you would hear the creaks and groans of the age-old timbers beneath you.

The wooden panels and handrails at the top were the first indication that you would be emerging into the type of courtroom straight out of a period film. In normal circumstances, the court did have all the pomp and circumstance one would have expected. The judge in his finest robes and wig, and the barristers buried beneath piles of official-looking documents, and bowing to the Crown as they entered or left the court.

The room itself boasted high, heavily corniced ceilings and elaborate light fixtures, with richly grained hardwood bench seats throughout. It was all you would expect of a courtroom of yesteryear.” [The Crum, 2013 edition, pg. 214]

With a jolt, you realize that the courthouse must be the derelict building you noticed earlier! It was closed in 1998, sold to real estate developer in 2003, and suffered two fires in 2009. Now no one seems to know what to do with the building, although there’s been plenty of talk.

Photo Credit: Keresaspa – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

With all the preservation work that’s been done on the gaol, and the famous trials that occurred in the courthouse, it’s a real shame that the courthouse looks so trashy.

Back inside the Crum, you retrace your steps through the tunnel and are given a whirlwind tour of the Governor’s office. Then it’s off to gaol itself, starting with The Circle.

All four wings radiate from The Circle, which made inspections quite easy for the Governor. The wings are named clockwise, with A-wing being on the left, B and C in the middle, and D-wing on the right. Each wing has three stories of cells, and a basement for supply and storage rooms.

As you take in the atmosphere of The Circle, your guide explains that the Victorians had some funny ideas about health and prison design. One of those ideas was that since the prison population smelled, the best solution would be to place the kitchens underneath The Circle, and use the huge air vents to pump the kitchen odors throughout the prison.

So not only did the prison smell of dank stone and unwashed bodies, it also smelled of nasty kitchen aromas. Yuck.

Before you venture into C-wing, your guide explains the gaol was decommissioned in 1996 because it was deemed uninhabitable. The roof was falling in, the original one-person cells were home to 2 or 3 men at a time, and inmates were still using chamber pots.

After four years of further decay, the gaol became a restoration project in 2010. Two years later, the roof was repaired, the barbed wire removed, and C-wing was restored to its former glory.

At the head of the wing is the Movement Officer, who had to log the movement of any prisoner leaving the wing in case of a security breach.

Next to his office is the Principle Officer’s Office.

It’s nothing more than a cell converted to an office. Definitely not the kind of place you’d like to spend 8 or 10 hours a day.

From here the P.O. would run his wing, overseeing 10-20 prison officers and reporting as needed to the Chief Officer or Wing Governor.

As you explore the wing, you encounter a bumper on the red tile floor.

The bumper has a heavy weight in the wooden base and was used daily by prisoners to spread red cardinal polish and shine the floors.

Past the bumper are a series of cells showcasing life in prison over different eras.

First is the 1846 cell, showcasing the prison as it looked at its opening.

Men, women, and children were all sent to The Crum when it first opened. This is how a child’s cell looked in the 1870s.

After 1860, it was illegal after 1860 for a child under 14 years old to serve his or her full sentence at an adult prison. Legal or not, children of all ages served part of their sentence in the Crum from its opening in 1846 through the early 1900s. Apparently the idea was to scare them shitless so they wouldn’t become repeat offenders.

There were some reforms in the early 1900s, just before WWI. Children and women were no longer housed at the Crum, and it became an all-male prison.

As the Troubles began in 1969, and internment without trial was reduced in 1971, the Crum became *the* prison in Belfast. Originally designed for 500 prisoners, during the 1970s and 1980s the prison was home to nearly 1400 inmates!

They were living 2 and 3 to a cell, like so:

You try to imagine how three people would live in just 84 square feet. Impossible to have any privacy, or move without stepping on your cell mate. Any time you wanted to use the bathroom or take a shower, you’d have to signal the prison officer, who may or may not decide to unlock your cell. At night, your only recourse was the chamber pot, which you or your cell-mates would have to empty the next morning.

Past the historic cells are the Punishment Cell, called “The Board” because by day all bedding was removed, leaving the prisoner with a Bible, water container, mug, and chamber pot.

Next to “The Board” is a genuine padded cell.

You’re near the end of C-wing now, and a frisson of excitement runs down your spine as Charlotte announces that the next stop on the tour is the double cell reserved for prisoners due to be executed.

Standing in the very room where the condemned men spent their last days, Charlotte describes the executions that happened here.

In its 150 year history, only 17 prisoners were executed at the Crum. All 17 were “stretched by the neck until dead.” All 17 had been convicted of a murder charge, and all 17 were male.

The first four executions were carried out in a specially-built gallows in the front courtyard. Although the general public weren’t allowed inside the prison walls, people gathered to witness the hangings in 1854, 1863, 1876, and 1889.

In 1901, a stone execution chamber with permanent gallows was added to the end of C-wing.

A man sentenced to death would first be transferred to the very cell that you’re standing in now about 48 hours before his execution. Two prison officers would keep him company around the clock, playing games, talking, joking, and drinking. Anything the condemned wanted to make his last days more comfortable.

On the morning of his execution, the condemned man was given his last meal and prepared himself for the walk to the gallows. Imagine his reaction when the back wall of his cell was pushed open and there, just on the other side, was the execution chamber.

The condemned man’s hands were tied behind his back, and his two prison officers led him into the chamber and used the smaller loops to steady themselves as they guided him into the noose.

After the condemned man was dead, his body would be lowered through the drop hole and into a coffin waiting below.

The body was then taken through a tunnel to the rear of the prison grounds and buried in unconsecrated ground. If they were lucky, a member of their burial detail would record their initials and the year of their death on the back wall near their grave.

Their families were not told of the date of execution and were not given access to their graves.

Before you enter the execution cell, your guide gives everyone a chance to back out of this part of the tour. Surprised, you realize that you are entirely comfortable walking into a room where 12 men were hanged.

Given its reputation as one of Northern Ireland’s most haunted buildings, you expect that standing not five feet from the nooses will bring on an experience like this:

“The atmosphere was oppressive and stifling and I could feel myself becoming physically sick with fear. The weight of despair upon my person was tangible, as if someone were pressing down on my head and shoulders, causing me real pain and discomfort. I tried to convince myself that I was being totally irrational, but couldn’t for the life of me shake it off.

. . . It [the trapdoor] was a very ordinary looking piece of apparatus, but my mind wouldn’t switch off, and I had to put my hand up to my mouth to avoid vomiting. I can only describe the feeling as one of sheer uncontrollable terror. So distressing was it that I felt close to running away, in a fight or flight type of reaction.” [Patrick Greg, The Crum, 2013 edition, pg. 44-45]

Amazingly, you feel nothing from the room itself, no strange vibes or creepy visions. Not in the execution room itself, and not in the drop cell below.

You do feel something as you’re the last person to exit the drop cell – a slight panic of being left behind that quickly dissipates as you follow Charlotte out of the prison and into the yard.

When you reach the unmarked graves, your guide points out several carvings in the wall. The clearest markings are S.McL 1961, marking the grave of Sam McLaughlin, the second to last execution at the gaol.

Close by are the initials H.C. 33, marking the final resting place of Harold Courtney.

Of Robert McGladdery, the 17th and last man executed on 20th December 1961, there is no sign.

Interestingly, the remains of all 17 executed prisoners were recently cataloged and tested for DNA markers. After more than 50 years of petitioning for the release of his body, the family and friends of Thomas Williams (executed September 1942) finally received his earthly remains from the Irish authorities in the mid-1990s.

A few years later, the family of Michael Pratley, executed in May 1922, also requested that his remains be released from the prison grounds. The request was granted.

Given the divisive political tensions in Ireland and the reluctance of any authority to change its policies, the fact that these two men were released to their families is quite poignant.

As you head back to the museum, it’s easier to see the scope of a prison wing in its entirety.

Your guide mentions that several escapes took place here. The first one took place in the 1860s, the last in the 1980s. Many more prisoners tried to escape but didn’t make it. Luck played a big part: some prisoners had it; others didn’t.

As you enter the gift shop, you hope to find a book that will bring the Crum to life. Although you enjoyed your tour, you don’t feel much of a connection to the place or the people who lived, worked, and died there. Since it is one of Belfast’s biggest tourist attractions, you’re hoping that some local author will have written a more personal book to bring the place to life.

You’re in luck. Tucked away in a back corner is a book called The Crum: Inside the Crumlin Road Prison. Written by Patrick Greg, the book details his fascination with the Crum and his reflections on his career as a prison officer in the Crum during the 1980s. It is part history, part interview with key figures who served time during the Troubles, and part Patrick’s own reflections on life as a prison officer.

Over the next couple of months, reading this book will give you a much deeper understanding of the building, its history, and the people who worked there, as well as its inmates. You’ll also find this video tour extremely helpful to supplement your own memories of the gaol.

For now, though, you have one final stop on today’s itinerary. After chatting with the gift shop cashier for several minutes, you emerge into the late afternoon sunshine and point yourself towards the Peace Wall.

Up next: first impressions of Belfast, Part 3: Civil War

Leave a Reply