July 24, 2016

The sanctuary stone is cool and rough under my fingers, the ancient paving stones uneven beneath my feet. My fingers follow an ancient ritual: for 1400 years, the stone’s carved cross has provided protection to those who seek it.

This is my first visit to Glendalough, one of Ireland’s most important monastic sites, and already the valley’s spirituality is sinking into my bones. The cobbled causeway under my feet dates back a thousand years or more. I’m placing my feet exactly where pilgrims, travelers, and visiting kings have walked for centuries.

Behind me is the gatehouse, where visitors placed all their wordly goods for safekeeping before entering the monastery walls.

A silver-haired woman sits outside the gatehouse. Her solo voice and haunting bagpipes become one with the sacred aura of the site.

Once past the causeway, the monastic settlement unfolds before my eyes.

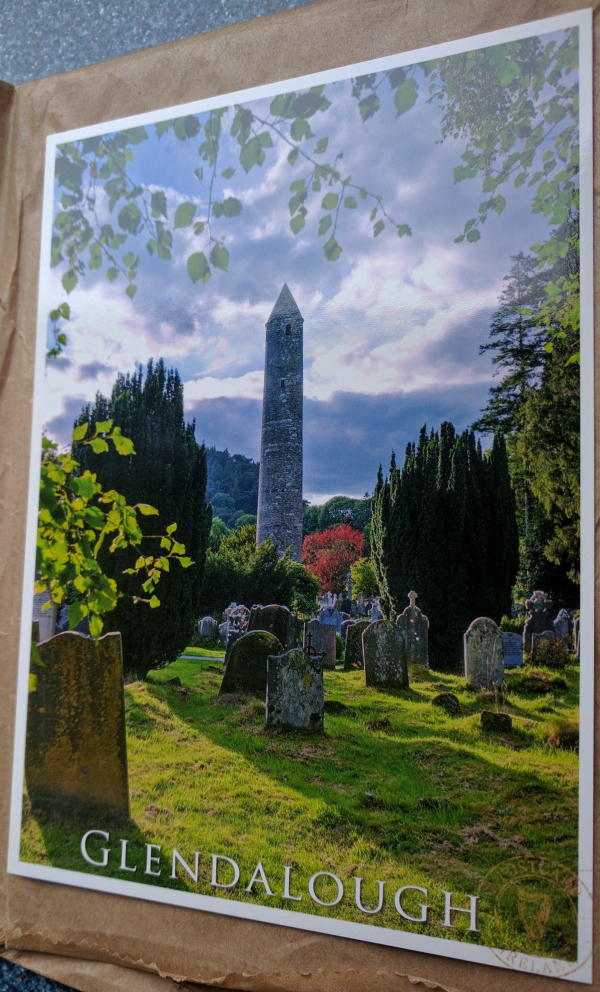

Like a needle on a compass, my eye is drawn to the round tower.

It dominates the settlement, drawing the eye upward from every part of the monastery grounds. It is easy to see why this tower is one of Ireland’s most iconic landmarks.

Nearly 100 feet high, with a door 11 feet off the ground, the tower has few windows to mar the smooth ascent of its walls. Four windows on the top story face the four compass points, allowing the bell mounted at the top of the tower to call the community to prayer.

Tradition tells us that towers like these were used as lookouts and a place to hide during an attack. However, our guide points out that the tower is essentially a 100 foot chimney. All it would take is one attacker setting fire to the tower, and everyone inside would die of asphyxiation or heat. A new theory is that the tower served as a landmark and storehouse rather than a place of defense.

Back pressed against the tower, I survey the monastic ruins. I wish I could see this place as it looked in its heyday. In a land with no settlements, what must people have thought of this bustling community? The numerous churches, outbuildings, scriptoriums, workshops must’ve seemed a beehive of activity to the average Gaelic traveler.

Something of that bustle exists today, with crowds of tourists and clusters of headstones so thick it’s a wonder there’s room to move among them at all.

In contrast to the thick stone forest outside its walls, inside the cathedral ruins there are only a few headstones.

It’s an impressive building, nestled at the heart of the community and dating from the 12th and 13th centuries. When I try to imagine the sheer amount of man power that went into building this cathedral, I cannot do it. How long did it take to find all these stones, transport them here, shape them to fit with the other stones, lift them up onto the walls, and figure out how to hold them in place?

One stone, in particular, has survived the passing of the centuries. Located near the altar, the cross inscribed on the stone slab is barely noticeable. But for those with keen eyes (or a keen guide), brushing your fingers over this stone is said to bring good fortune for the rest of your life.

Next to the fortune stone, a break in the cathedral wall leads to St. Kevin’s Cross.

It’s a massive sculpture: 7.5 feet tall and carved of a single block of granite. It’s not elaborate or fancy, but its sheer size and weight give it a palpable aura of timelessness and strength.

Local legend says that if you stand where my guide is standing, lean into the cross and wrap your arms around it so you can touch fingertips, then tonight you and your true love will dream of each other.

A narrow footpath through the gravestones from St. Kevin’s Cross to the Priest’s House. It’s a tiny, two room cottage, barely big enough for a bed and a fireplace.

Some historians speculate that it may have been used to house St. Kevin’s relics. Others think it was used as an infirmary hut, a place where a monk could remain near his sick patients or a place for sick monks to sequester themselves from the community. Our guide says that St. Kevin is thought to be buried beneath its floor; the wall plaque says it was used to inter priests in the 18th and 19th centuries, which lead to the name “priest’s house.” It’s impossible to say which of the theories are correct. I like to believe they all may be.

Past the Priest’s House is a smaller, tidy section of cemetery. It is the family burial plot for the Kings of Leinster and extended family. St. Kevin, Glendalough’s founder, came from this ruling family. When he decided to start a monastery in 600 AD, he did so on his family’s land at Gleann da loch (valley of the two lakes).

Glendalough became one of Ireland’s most famous monasteries and centers for learning until the Normans destroyed the monastery in 1214. After its destruction, the dioceses of Dublin and Glendalough were united, and the center of learning and church activity moved to Dublin. Glendalough served as a local church until the settlement was destroyed by the English in 1398, and remained a place of pilgrimage even afterwards.

Throughout all these changes, members of the King of Leinster’s family continued to be buried in a reserved section of the monastery grounds. The most recent gravestone bears a date of 2013, just three years ago.

Beyond the Leinster graveyard and hidden by a thick hedge are the remains of the abbey and nuns’ quarters. To the left is St. Kevin’s Kitchen, and beyond it a stream running along the valley floor from the nearby lake.

A hiking path draws me over the stream and onto a wooden boardwalk. Soon the sounds of my fellow day trippers fade into the misty grey air, and I am alone.

Ahead of me a blanket of cloudy mist obscures the upper part of the valley, while behind me Glendalough’s round tower is blends into this peaceful, breathtaking landscape.

To my right the valley floor begins to rise, but to my left I have a clear view of the lower lake.

A muffled stillness hangs over the entire valley, broken now and then by the thud of boots or sneakers on the boardwalk, or shouted laughter from tourists on the other side of the lake.

Past the lower lake, the boardwalk is enclosed by forest. I am admiring the mossy trunks when I suddenly realize I’m not alone. A wild deer is grazing not five feet ahead of me.

A second deer is nearby, reaching on its hind legs to eat the leaves off the low tree branches. They are unconcerned about human traffic on the boardwalk, but I hardly dare to breathe for fear they’ll take flight. I am captivated by the strength and speed that lies within their bodies, by their elegant lines and graceful movements.

The boardwalk continues to draw me deeper into the forest. It’s hard to believe that anything can be more breathtaking than the wild deer, the mist hanging over the hills, or the monastery ruins themselves.

And yet, when the boardwalk spills me out at the shore of the upper lake, I find I am gloriously wrong.

Any moment, a fairy might descend from the clouds hanging low over the valley or crack open the neighboring hills.

A Gaelic war party could thunder down to the water’s edge to water their horses, or a siren rise up from the lakebed and lure them to their deaths.

A gaggle of peasant children might dare each other to hop from stone to stone, while their mothers scrub shirts in the spring nearby.

If I could, I would happily spend all day exploring this valley. It is a peaceful, serene place, full of mystical possibilities and stories that are waiting to be written. If only I had some talent for fiction writing, I would bring this place to life in story after story.

It’s the kind of place that stays with you long after you’ve boarded the tour bus and driven away. The kind of place you’d come back to over and over again, and expect it to be exactly as it has been for hundreds of years: a place of refuge, of spirit, and of history.

Up next: a whirlwind tour of the Wicklow Mountains and the medieval town of Kilkenny.

Nice — given my historical bent, scenery that I appreciate… The “Sika deer” was a nice touch.

The “arms around St. Kevin’s Cross” legend is interesting, given that he was thought to be an aesthetic, drowning a woman for attempting to seduce him (before “Just say no”, I’d guess)…

Maybe St. Kevin’s actions re: seduction inspired the “just say no” campaign. The scenery at Glendalough is incredible. I would love to go back alone (if such is ever possible) and sit awhile in the peace and history.